The yellowing map that was compiled of brutally dehumanizing acts of violence across the United States from the start of the last century presents what seems another country. The preponderance of dark splotches marking incidence of such outbreaks like a pox not only suggest the deeply rooted nature of a radicalized terror we must confront. Their spread possesses an alarming–if not terrifying–correspondence to the relatively sudden spawning and foundation of privately held prisons across identical states. In ways that reflect the difficulties of imagining clear social consensus, and at the same time reveal the ugly divides in attitudes to individuals, the map that compiles the occurrence of lynchings seems not to be only a removed archival record, but a seems an actual precedent for the race-based nature of mass incarceration in America today.

The spate of such privatized prisons and institutions of confinement seek to balance the actual overcrowding that plagues most state-run circular facilities today–facilities that are stained not only by outbreaks of disease, unjust incarceration of the mentally ill, violations of human rights, and overcrowding and unsanitary conditions. But even as the institutionalization of dehumanizing violence that seems to have disappeared all to readily from public view has left deep psychic scares in the country in ways difficult to map or even gauge as what can only seem a one-time normalization of racialized violence, and if such crimes against humanity pose steep challenges to comprehend, the question of their remove–and whether the past is ever dead, or even past–is raised by the realities of racially biased incarceration that contemporary society still seems to tolerate.

The yellowed map remains so heart-breaking as to seem what may be a foreign country in the openness of racially motivated violence, to be sure: the image that maps all lynchings that were recorded in US states and counties from 1900-1931 record a widespread dehumanization in the fairly recent past, but seems a landscape of hatred–and racial animosity–that has receded into the past, and that few could imagine or acknowledge any social proximity. The national map, based on research of the Tennessee-Based Tuskegee Institute for the early twentieth century, or just years after the journalist Ida B. Wells in 1895 had tabulated the widespread phenomenon of lynching blacks in the 1890s, pictures a nation so consumed with hatred and vigilante violence to seem far removed from our world–as if truly foreign country, the widespread frequency of lynching over three decades that it maps suggests a terrible if tacit sanctioning of public violence and violent dehumanization directed largely against blacks. The barbaric dehumanization may appear confined to certain region that one would want to demonize as different, but the breadth of its generality from Louisiana to Arkansas to Texas to Georgia to Florida and to Virginia is truly terrible and mind-boggling to comprehend–and only based on the availability of data. Must must have been lost, or hard to confirm.

Similarly challenging to comprehend, as Bryan Stevenson has noted, is habituation to a landscape of violence that must have been the intentional and psychically indelible result on blacks. The distribution of cases of lynching across early twentieth century America reminds us, terrifyingly, of an acceptance of such an extra-legal institution of racist persecution. It hits us, with the visceral shock that, allegedly, the then-Malcolm Little felt when he first heard Billie Holiday sing the signature “Strange Fruit,” a meditation on the rash of lynchings in the South, after arriving in New York City. Holiday evoked “black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze” in ways by which the future Malcolm X was deeply moved at their lamentational refrain describing the dehumanization of blacks. The yellowed map provokes a similar punch to the chest, iasking its viewer to recognize a country where a dehumanizing hatred was widespread, and lynchings regularly occurred across the “gallant” South that Billie Holiday evoked with spooky bitterness.

The spectacle of the hideous violence enacted by vigilantes on black bodies seems most densely concentrated in areas of deep south–most especially in Georgia–but a large area of “southern trees” span the fields of Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas and South Carolina, where racial hatred and uneasiness had deep roots and provoked profoundly deep social anxieties at challenges to social segregation. The practice of lynching seems to have been clearly tolerated further north and further west to Washington, Utah, and even California, forcing us to consider the expanse of the “strange and bitter crop” we often locate in a time so removed from our own. Such a strikingly expansive geography of organized vigilantism and improvised executions across so much of the United States now seem difficult to comprehend–going far beyond racism in their distancing of men as others–as the familiarity of dehumanization it implies was a forceful distancing of oneself from others’ lives and experience, and readiness to exempt them from a universal system of justice.

But is it only a historical coincidence that a remarkable geographic concentration of both the growth of federal prisons from 1950 and of rates of incarceration mirrors the distribution of lynchings both along the southern Mississippi and in western Florida–two sites of the greatest growth of federal prisoners? The echo of exclusionary disenfranchisement is more than eery: for if the number of lynchings seem focussed to some extent along the Mississippi River, from Arkansas to Louisiana, South Carolina, Alabama, Georgia, Texas and Florida–the map is based on recorded data alone, and must exclude or omit what lies outside recorded lynchings that, if the victims of mob violence were white or caucasian victims in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, were overwhelmingly African American in majority from 1900–and rarely perpetrated on few whites from the 1920s–suggests that we re-examine this Tuskegee Institute map against the patterns of incarceration with which our country is now also plagued.

The even greater detail of a similarly heartbreaking distribution recently and more authoritatively delineated by the Equal Justice Initiative’s survey of a full seventy-three years of lynchings foregrounds premeditated vigilantism aimed at African Americans, and predominantly in Southern States, that claimed some 4,000 lives of their victims in a far more extensive manner than previously believed–wildly incommensurate with the relatively minor infractions which inspired a brutality and level of atrocity that responded more to anger at apparent violations of the segregated status quo. The map that Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative released greatly expands earlier lists released by the Tuskegee Institute from 1912, and includes previously unreported collective massacres similarly intended to terrorize local black communities through what can only be described as a culture of extreme violence across the Old South:

Equal Justice Initiative (source)/Visualization and graphic from New York Times

The emergence of such a landscape of violence across southern states over the years 1870-1950 suggests the extensive nature of brutally performed executions that were no doubt designed to terrorize the population, far beyond retributive justice as public spectacles of violence that were acted out on black bodies: the troubling levels of such violent executions reveals strikingly sharp concentrations at sites across the South where blacks were most subordinated–along the Mississippi, as well as in Alabama, Georgia, and northern Florida–and insubordination feared. The distribution of such popularly sanctioned violence against blacks no doubt reflects the concentration of populations of blacks in the deep Southern United States by 1950, with a few exceptions, even after the great migrations to New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles, and suggest the reality of a landscape of terror from which many blacks able to do so removed themselves:

Library of Congress

The expanded evidence of sustained patterns of such violently dehumanizing practices of lynching–at times in reactions to race riots, as in the densest site of the atrocity, and most densely in Louisiana, reached numbers so astounding that they cannot capture the habituation to violence based on “racial terror,” and indeed the unleashing of something like a repressive dehumanization that has been historically underestimated in its expanse. Stevenson suggested the very long-term effects of how “the lynching era created a narrative of racial difference, a presumption of guilt, a presumption of danger so readily assigned to African Americans in particular–and that’s the same presumption of guilt that burdens young kids living in urban areas who are sometimes menaced, threatened, or shot and killed by law enforcement officers.” Does the spate of the construction of jails in many of the same regions suggest something of a similarly misguided–if by no means as openly violent or explicitly dehumanizing–a disproportionate strategy of response?

If the past is indeed a foreign country, our country retains an institutionalized ‘othering’ of criminal populations that has come to fulfill similarly monitory functions if not similarly terrorizing roles, that run against our better instincts. The ongoing expansion of institutional structures of imprisonment might however be compared to the geographic multiplication of lynchings in the early part of the twentieth century, as a similarly misguided attempt at justice. Although density of the concentration of lynchings across the Southern states evocatively mark a vanished record of openly sanctioned violence of vigilantes and murder, the proliferation of jails in some of the same regions of the country raise questions about the widespread acceptance of practices of imprisonment in contemporary America. Although imprisonment removes felons criminals from the public eye, the widespread acceptance of practices of imprisonment in contemporary America seems haunted by a distance from humanity analogous to the normalization of the vigilantism of earlier times. Indeed, the belief that crimes of immigration, drug possession, or other non-felony offenses merits excluding persons from civil society by mass-incarceration, and the collective incarceration of African Americans in which this results, seems more than eery sense of continuity with the past.

For the map made from findings of the Tuskegee Institute and printed by the by the American Map Company circa 1931, presents a troubling distribution of the social ills of the inter-racial hatred in early twentieth century America. The map, based on the decision to compile data on lynchings at the prescient decision of Booker T. Washington, shows Georgia and Mississippi at the top of the cumulative tally of such a vigilante justice, the locations of the vast majority of which are known, resonates with maps of slave-owning some two generations prior. It also offers something of a historical perspective on continued state-sanctioned violence of correctional authorities against imprisoned felons in America today–and perhaps a window into how we are able to turn the other cheek to a pronounced widespread ‘othering’ of a large population of the nation. Mapping of the spread of mass-incarceration and prison construction suggest a shadow of the terrifying precedents of the absence of legal protections for all citizenry, and readiness to marginalize members of society and to suspend civil protections. The distribution of imprisoned Americans and the costs of imprisonment document a similar image of the scars and severe social costs today–judging only from the topographies of prisons and imprisonment in the United States.

Wikipedia: prison incarceration rates by state as of 2008; based on statistics from US Bureau of Justice

The map strongly contrasts to the actual localities of highest crime, as compiled from an FBI Uniform Crime Report, of 2012, despite some similarities: indeed, the contrasts are even more apparent when it comes tot eh contiguous darker states of high incarceration in the southernmost states.

1. The occurrence of lynchings that we can track like a pox from a century ago might go some way to explain striking reluctance to abandon state-sponsored executions of the imprisoned in America’s legal system. The willingness to turn the other cheek to demonized populations by excluding them from either civil rights or legal protection of their persons even suggests a sense of the validity of imprisonment that stayed with us in the disenfranchisement and expulsion of those classified or tarred as felons. For our prison system seems, as we look at it in detail, to operate outside of the sense of individual rights we imagine a legal system would secure, and reveals a strong sense of excluding demonized members of our society from the social order, out of the belief that incarceration is the best service we can offer. This is a question that we might do well to revisit, especially when we consider the widespread evils that a socially sanctioned system of particularly violent retributive “justice” held across several generations in many counties across the United States.

Maps indeed condense pictures of nations. The national maps of incarceration offer a troubling image of our civil society, whose system of justice seems to tug at its seams of civil society as we direct increasing funds to maintaining a carceral state across the country. Is the perpetuation of an expanding system of imprisonment and prison construction a vicious cycle with terrifying historical precedents? Have we expanded our prison system, even more bluntly, in ways that provide a rationale for a new violence of social exclusion?

As US courts continue to imprison more folks than China–a nation whose population is nearly four times our size–the attempt to believe we are able to control the spreading number of imprisoned, and to continue to deny prisoners any rights, suggests a greatly diminished notion of the social good. The provide something of a map of a masked immobile population, relocated from the cities to marginal areas in upper New York state, northern California inland, southern California desert, southern or central Texas, or southern Florida coast, too easy to be forgotten even as we watch, only somewhat guiltily, multiple seasons of “Orange is the New Black.” For while we are watching sequential seasons of the social interaction among inmates, we are acknowledging both the thin line dividing characters and a carceral system and reaching into the life of imprisoned, voyeuristically, attracted by the ability to cross a dividing line between the imprisoned and those out of prison we don’t often traverse: the inmate-inmate sociability among women we almost seem to know in orange is all the more engrossing because of the setting in Danbury prison to chart the social topography of a foreign land where we like to think of ourselves as unlikely to go.

2. A set of infographics on the social costs of the meteoric expansion not only of prison populations, but of almost improvised solutions to deal with prison costs, will suggest not only the serious social costs of the continued expansion of mandatory jail sentencing, but the extent of social violence and disturbances that the institutionalization of such sentencing–and of sentencing of young kids to Life Without Parole–has already produced. The maps of jails and practices of imprisonment across the country show not only a sort of sanctioning and sublimation of a similarly oppositional rhetoric but also their institutionalization. Maps that locate the changing distribution of prison populations or provisionally released parolees across the nation and state of California–and in urban communities–should send a number of red flags about the sort of society that our tax dollars are working to create through the expanding possibilities of incarceration. The expansion of the prison industry within the United States has long won widespread ire of many, but has also increasingly been mixed or seasoned by a growing sufferance of the unequal distributions of the prison populations and demographics.

The overt if passive tolerance of the evolution of a system of imprisonment and as a society apart, defined by its own operations, protocols, and possibilities of employment and economic viability within the United States is something akin to a cancer eating at civil society. “Mass-incarceration on a scale . . . . unexampled in human history is a fundamental face of our country today,” as Adam Gopnik observed back in 2011, and has created a bizarre social map threatening to warp the civil fabric and government alike. It is no coincidence that the almost routine nature of carceral practices and prison sentencing is at the cry of in the television dramatic comedy “Orange is the New Black,” which traces the lives and fate of women imprisoned on drug charges who we would not “expect” to follow behind bars. In the Netflix series, a correctional facility re-appears as a soundstage, in a bizarre sleight of the unconscious where the socially repressed preponderance of imprisonment returns, or the marginalized becomes a stage filled with characters with whom we identify. We become the complicit audience and spectators: the show’s broad appeal may well rest in how the following maps of the huge growth of incarceration has dramatically affected our national fabric.

Maps are compelling media to process the reality of incarceration and its hidden and actual costs, and help to confront the huge social costs of the very processes of dehumanization we often want to hide–but risk to create very lasting social and humanitarian dangers. For we similarly rarely observe either the social costs of the scale of imprisonment that we have undertaken across the fifty states, or the expansion of what stands as virtually a separate state of the incarcerated–a state devoid of civil rights or voting rights, but which is not only increasingly silenced, but which we do not want to recognize. In a manner similar to which lynching was a silenced rite of violence in much of the south and elsewhere that was rarely recognized–witness the power of Billie Holiday’s song, Strange Fruit, composed by Abel Meeropol, after he was so haunted by photographs of lynchings that led him to compose the song in 1939–until society was made to face its sanctioning of mob-based violence and outright cruelty. When we look at the percentages of imprisoned in some of the very same states, we cannot but continue to flinch.

3. From an implicit tolerance and acceptance of crime as a part of daily life in urban society, over three decades the United States has transformed to an incarcerating society of proportions that have never been known before. Prisons are increasingly constructed across the country to house increased number of prison sentences handed down: their construction is not based on the changed the character of justice, but made prison a procedural part of policing criminal activities, with the result of shifting our social topography more than the economic recession. In ways that seem to offer para-urban societies of imprisoned life, prison life has emerged as a false compartmentalization of social actors. This division corrodes the social fabric and may well derive from an obsession with the procedural operations of the law that culminate in the legal naturalization of the process of incarceration. William J. Stunz implied so much in his Collapse of American Criminal Justice, where he tied the new legal culture that promotes the dominance of incarceration to the institutionalization of a terrifying proceduralization of meting justice, that privileges process over individual rights. If mass-incarceration is the United States has become a part of criminal policy across many states, the criminal system, Professor Stunz argued, is as much at fault for the adoption of jail sentences as part of confronting crime. The increased reliance on incarceration–and the dehumanization of prison populations held in not only unsanitary conditions but with poor medical attention–create a situation rife with overcrowding, squalid conditions of life, and little structure or actual occupation for inmates’ time.

The Centre for Prison Studies at Kings College London nicely distorts a Robinson projection to show the hugely distorted proportion of their population of imprisoned populations as of 2010, shading nations in darker hues in correspondence with the percentage of its own citizens the country jails, in ways that not only bloat the United States’ landmass, but shows it to be the country that imprisons the greatest share of its population–over 700 per 100,000–surpassing, in so doing, either Cuba, South Africa, or Thailand, as well as the Russian Federation and China. and suggesting the broken nature of our addiction to imprisoning our fellow-citizens.

International Centre for Prison Studies/Kings College, London

The increasingly poor conditions in the US prison population are, for now, not able to be mapped–no doubt because of poor availability of data. But the poor conditions in the carceral state in the United States parallels both the increasing expansion of a prison system and the privatization of prisons as centers of “managing” imprisoned populations, often including solitary confinement and other abusive practice, rather than responding to rights of humane imprisonment–as if the construction were not an oxymoron.

The global context of our habituation with imprisonment however conceals the relative readiness of certain states are ready to treat their residents, but and the clear domination of southern states–“Red” states?–to a policy of zero tolerance, or readiness to look the other way in ways that provide . The map conceals the fact that the greatest growth of prisons in recent decades, between 1979 and 200, occurred in Texas (706%) and Florida (115%)–which show ample deep blues of a rich culture of imprisonment–but also New York (117%), California (177%), and Georgia (133%), where imprisonment has increasingly emerged as a way of life, in ways tat seem independent of political parties. Perhaps this arose from anxieties of immigration in the first two states–Texas saw 133 prisons built in 2000 alone; Florida 84 and California 83 over the same two decades–but building of further prisons to house an expanding number of imprisoned has become routine in our national justice system: Minnesota built 60 prisons; Georgia 42; Illinois 40. Was imprisoning not in some way seen as a way of reorganizing society by 2008?

The annual cost of $5.1 billion in prison construction in 1995 alone to feed this growth of mass-incarceration is unable to be sustained.

Wikipedia: prison incarceration rates by state as of 2008; based on statistics from US Bureau of Justice

The uneven concentration of prison populations in much of the United States reflects the distinctly larger likelihood that rural populations will be sending their populations to prisons that has risen markedly from 2006 to 2013, with a considerable decline in the numbers of prisons from larger cities as Los Angeles–a decline of 69%–and San Francisco–a decline of 93%–which suggests not only a greater gentrification of the city, which may explain the considerable if lesser reduction of people sent to prison in Brooklyn as well in this period–37%–or Durham, North Carolina–

–but a clear sense of “keeping it safe” in many counties that maintain their own policies and practices of active persecution, as noted Peter Wagner of the Prison Policy Initiative, which determine how the punishment fits the crime.

Indeed, the privatization of the process of prison construction in the United States has led a greater amount of prisons to be built in the country than Stalin built in Russia, and has defined us as the paragon of the incarcerated society. Rose Heyer created stunning map of US prison proliferation from 1900 to 2000 for the Prison Policy Initiative, represented the United States at the International Cartographic Conference and Map Exhibition in 2005, charting the growth of populations housed across the country in federal prisons from 57,00 to 1.3 million. The result reveals the hidden population of a lost metropolis that is dispersed across the country–whose demographic size rivaled (and now surpasses) the population of the city of San Diego, but are located behind bars across the country, often removed from cities, whose expansion suggests a negative nation within our own:

4. How to process the map of growing incarceration–or indeed map the terrifying phenomenon?

Composer Paul Rucker has crafted an eery performance piece about “the proliferation of the US prison system if seen from a celestial point of view,” animating the augmentation of prisons across the nation through 2005, echoing Heyer’s map, that concludes with in an image documenting the infestation with practices of incarceration: if light green beacons dot the country with prisons through 1900, yellow dots spring up after 1940, and then morph to orange dots through 1980 in a sequence of pulsating lights that mark prison foundations in ways increasingly difficult to process or get one’s mind around as a growing landscape of confinement. The topography of sanctioned violence against individual offenders may be concentrated in the Deep South for multiple reasons. But it corresponds to a map of the willingness to see criminals as ready for incarceration that oddly echoes the landscape of income inequality across the country.

More striking is the shift in the topography of US Federal prisons across the land since 1950–when prisons were concentrated in but a few states, and understood to be marginalized from the body politic–boggles the mind: we live in an era of prison-contracting, marked not only by a growth of state prisons, but widespread practices of incarceration.

What has happened? If the spread of prisons map somewhat onto the nation’s major cities, the overlay of red dots that suggest dots of blood marking prisons built from 1981 to 2005 seem to suggest a spread of smallpox or toxic pustules across the land, as the spread of incarcerating institutions finds its counterpart as wistful cello bowing gives way, as the nation reddens as clear regions of penal proliferation gives way, to the current image of the nation in his multimedia performance, and a plaintive cello to concludes with electric bass guitar and snare drums, offering a frustration and rage against the institution of incarcerating institutions, as much as a mode to contemplate the contours of this new status quo. The accompanying soundtrack of the multimedia presentation compels attention to the conditions of life for those residents of the expanding carceral state that now confines a surprisingly sizable proportion of the residents of many states–and over 3% of its total residents nationwide, according to a meme that has circulated on the internet, if, just as terrifyingly, it seems to reflect African Americans as much as the general population. Already a decade ago, many states were approaching or at a situation with 5% of their populations under control of prisons or criminal justice.

Rather than lie concentrated in an archipelago of incarceration, the web of prisons house over 1.5 million inhabitants is a true pox upon our houses, but embodies a large population of imprisoned, spread across the nation in legally sanctioned confinement.

Try to track the same impending expansion of practices of incarceration in dramatic progression, follow Rucker’s transfixing musical meditation on the “celestial point of view” on confinement–

[youtube+http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ySH-FgMljYo]–

to its conclusion, and try to distance yourself from the massive assault on civil liberties that is perhaps its primary consequence. The terrifying dimensions of such a carceral expansion remaps the country as a center of confinement, as much as an embodied territory. What happens to the hidden population as a result?

5. The dramatic dehumanization of prison populations raises fears of a crisis in health, mental health, and empathy whose impact has still not been fully felt for many other residents in the country. Yet the impact on the country cannot be denied: “Orange is the New Black,” a retelling of the true story of Piper Kerman, serves as some sort of barometer of the national subconscious, by which to come to terms with the expansion of such routinized imprisonment as a way of managing populations. The prison system, indeed, has expanded to provide a system for the geographic dispersal of criminal populations into private prisons that is as striking as the spread of institutions of incarceration across the land. And among those imprisoned, the rise of imprisoned women by some 646% between 1980 and 2000–or over double the rise for men, according to the Sentencing Project–our prison population has slowly begun to demographically change, the large majority of women being sent to state and not federal prisons for non-violent offenses. The show’s huge popularity rests on the degree to which prison-life can change the structure of many American families, but how we’re increasingly apt to not know prison society or to even take the time to examine its structure.

The multiplication of prisons across the nation, paired with the habituation of sentencing to jail terms, has created deep social stresses across most of the most challenged communities, most vulnerable to dropping out of high school or fragile family structures where single parents are unable to support kids to the extent that they need. The “system” has begun to redistribute prisoners across the nation, leading prisoners to often be shifted, on account of the exiling of local prisons or closure of older sites, hundreds of miles from their homes and possibilities of family visitation, like prisoners in Washington, D.C. who are routinely sent to prisons in Texas, Florida, or California after the closure of the Lorton, Va., prison which formerly housed them in ways that radically increase the probabilities of recidivism, basing oneself on statistics from the Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency of Washington, D.C.

The odd expanse of the distribution of D.C. offenders throughout to some twenty-six states nation-wide is not completely atypical for the broad redistribution of inmates in federal prisons in the frequent separation of families in ways that militate against visitation rights.

One can get a similar snapshot of the removal of kids from their parents that acute levels of imprisonment and incarceration generates in this map of children of imprisoned populations in Illinois prisons, in a geomapping of those receiving assistance from the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services based on a Statewide Provider Database, breaking the state’s prisons into their racial composition in relation to those children and youth who were in the database from 2009: the result shows the dislocation of parents from their kids, the isolation of children at an age vulnerable to high drop-out rates, and the vulnerability of African-American families.

6. And what of the current proliferation of privatized jails, institutions which suggest not only the monetization of imprisonment, but even, in building their economy on institutions of imprisonment, perpetuate an effective incentivization of imprisoning felons? The augmentation of the number of prisons run by private agencies–contracted out by the state–in a practice that rapidly increased since 2000 in the G.W. Bush administration so that institutions of incarceration now cost the country upwards of $50 billion to administer and run, and have come to be part of states’ local economies. The rise of private prisons in our society has grown to some extent independently from rates of imprisonment, as they almost seem to generate a false need for practices of incarceration, as multiple contractors of prisons have come to meet the demand in multiple growing states, and not only because they are legally guaranteed to turn a profit.

Although many prisoners were assigned to build military materiel during World War II, to compensate for the shortage of working men, the expansion of such for-profit entities with independent voices as corporations and lobbyists suggests something like a system of displacing costs and balances, an idea with one foot back in the industrial revolution, and another in the notion of paying off exorbitant costs generated by the criminal justice system itself–inserting the expanding number of prisoners in a market for cheap labor that can compete for jobs sent off-shore, oddly congruent with conservative demands to downsize government costs. The dramatic expansion of private prisons are, for the most part, though not entirely, concentrated in the southern states: Florida, Missouri, Arizona, Texas, and the trio of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, the top three states most likely to send their population to prison, are the places most likely and ready to send their citizens to prison. The emergence of such for-profit groups as the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) or GEO Group constitute not only massively powerful forces of federal lobbying, investing from 1.5 to 3.5 million dollars in backing legislative efforts to expand imprisonment, and sentencing terms, but to redefine the notion of criminality in ways that are in danger of undermining our democratic values. Both corporations are publicly traded, in a perverse exploitation of practices of imprisonment as money-making ventures. The GEO Group happily describes itself in corporate newspeak as “the first fully integrated equity real estate investment trust specializing in the design, development, financing and operation of correctional, detention, and community reentry facilities worldwide,” casting itself as an optimum source of investment, rather than as an institution that benefits society or counters crime: the odd perversion of the rhetoric of institutions of hospitality masks the experience of the prison as a profit-making exercise, somewhat analogous to the workhouses from the 19th century industrial revolution.

Such prisons market themselves as sites of investment at the same time as they constitute something akin to legalized sweatshops, which sanction slave-labor type conditions, unregulated and un-unionized,without overhead, that perpetuate violent sites of prisoner-prisoner violence as well as abusive relations to prisoners, and a virtual race to incarcerate in order better to exploit the incarcerated.

While this map focusses on three companies of “private prisons”, in the state of Texas alone, the number of privately run prisons boggles the mind, and lead one to wonder how their expansion can imagined to respond to an actual public good:

The extent to which the expansion of such private prisons is now embedded in our local economy has actually influenced members of the US Congress of both political parties, quite recently, to reject the “Deutch” amendment to ease requirements to detain 34,000 undocumented immigrants each night to continue to receive federal funding:

Talk of a “prison industrial complex” is not far off, as an invisible republic of prisoners stripped of rights and humanity has been institutionalized with startling rapidity across the nation, where a growing percentage of residents live in confinement. The rise of prison labor, working for as little as .23/hour, which are organized by corporations like Unicorps, founded by the Federal Department of Labor, based on prison labor, based on “nation-wide locations” that can outsource labor “at offshore prices.” Such an effective acceptance of incarceration as a vital part of local economies distinguishes the United States. It not only leads to the exploitation of prisoners–and the consequent perversion of a system of justice–but includes the standard the practice of paying inmates less than $1/day or less to package meals for inmates at other prisons or putting defendants not able to pay court fees–especially in immigration cases–in prison as a result. While cutting monies to enforce federal standards for the Prison Rape Elimination Act, states are opting out of monies that might offer recourse to prisoners for abusive conditions, at the same time as “trying to squeeze money out of defendants once their involved with the system, rather than trying to save money by keeping them out of it,” as Dara Lind has noted. “They come to America to steal our jobs, so we arrest them to do our jobs,” as Stephen Colbert put it in his recent “Debt or Prison,” relieving costs of incarcerating folks by using them as cheap labor to make meals, scrub showers, or make products, even by ostensible felons who are imprisoned for not being able to pay court fees–creating a system of making more prisons whose cost can be covered by work done by imprisoned, resolving debt by imprisonment in ways akin to workhouses or forced labor.

7. It is important to remember that imprisonment offers itself as something akin to a national epidemic. Placed in a broader context, the rise of prisons across the land raise red flags about the sad state of the anomaly of our incarcerating society. The global willingness to incarcerate populations reveals how this lopsided choreography plays out in the global stage, however, and raises some eyebrows about the readiness of our institutional use of prisons across the country, if we didn’t need the living example of Guantanamo Bay as an example of how hard it is to wean ourselves from the incarcerating operations so common to American life as a way to settle social disputes–creating outsized populations of prisoners in such places as Guantanamo Bay, like Panama, Guadeloupe, St. Lucia, Barbados or Martinique. According to the US Bureau of Justice Statistics, American jails hold 25% of all prison inmates on earth. How did prison become such a readily institutionally accepted part of our society and legal system? Does America offer a model from which the culture of incarceration has diffused?

A cartogram of imprisonment devised by The Society Pages, to inflates the size of countries with the greatest incarceration rates, and shrink those countries which incarcerate fewer than 150 per 100,000 people, and expands the United States to Brobdingnagian proportions:

The swing toward ready imprisonment–and the ready criminalization of behavior or reliance on a prison system to absorb the marginalized, despite the clear dangers of incarceration both to psychological health and well-being, as well as to human compassion, suggest a looming crisis in our belief in a system that is not really able to help us in the end. Since the year 1980 alone–when I was about to start college–the social costs of sanctioning such an expansion of practices incarceration seems staggering. If the continued growth of incarcerated individuals is pursued in the belief that it can solve social ills that have been barely addressed, its e cost to our society demands to be calculated.

Has any other nation ever been able to afford the costs of incarceration that such policies dictate? At a cost of 24,000 per inmate per year, the costs of incarceration are perhaps most gravely social, but increasingly financially infeasible.

Wikipedia

Our current rates for incarcerating youth are as strikingly disproportionate, raising even greater fear of the dangers of our penal addiction:

The spread within our justice system of the initials “LWOP”–sentencing to life without parole–seems a fit between the need to house criminalized populations and the expansion of an true economy of incarceration, where the only chance to make sense out of the national population guilty of crimes is to incarcerate them at considerable national cost. (Prisons bring real jobs to a city, including not only guards, but food services, sanitation workers, drivers, and an injection of federal or state monies, as well as, in the short-term, construction jobs.) The topography of Life-without-Parole sentencing across the nation is a particularly unseemly sight when we realize the current institutionalization of the sentencing structure across the states, to which New York, Indiana, Kentucky, Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Montana, Oregon, California, Alaska are the only exceptions across fifty-one states, across which life sentencing of youths in Florida and Louisiana seem shockingly high and almost legally accepted by courts:

We all know that growing up in a prison is not the best site for emotional development or health care, the legally sanctioned expulsion of incarcerated from our society has grown, increasingly strong and widely accepted as the consequence of felony: felons are disenfranchised so widely that in much of the nation poses a real threat to their civil rights. Most all states deny to prisoners the right to vote, and many extend that to periods of probation or parole, to the extent that over 6 million votes are excluded–even as conservative groups have seized on prisoners’ voting as the number one form of voting fraud. With about one in every 33 American adult citizens in jail or prison or on parole–in some form of correctional control–in 2013, the end result is a massive act of disenfranchisement that potentially undermines our democracy and democratic values:

The potential long-term disenfranchisement of African American populations who are routinely sent to prison for lesser charges, or to those charged with illegal immigration, poses long-term difficulties for our civil society, as well as on our sense of community.

8. This is true on the level of states, as much as a national level. Local populations of the imprisoned have strikingly deteriorated over time, as states have not been able to keep up with the sentencing of criminals to prison terms or life without parole. Even though we saw record-high numbers of prisoners in most states in 2008, when the quintupling on prison expenditures seem to have been first noticed in infographics, the large prison populations in California, the the increased tendency of states to lower prison rolls has hardly reached federal prison. A record high number of Americans still seems to continued sent to prison, increasing the number of imprisoned Americans for the first time in history to 1 in 100.

To take one example, the tremendous growth in the prisons of the state of California, once considered the pride of the country, has responded to a rage of procedural sentencing–in part due to the acceptance of a new law that allowed victims of crime to speak at parole hearings of an incarcerated, in ways that reduced chances of parole, and allowing the state’s governor to overturn parole board decisions. And the notorious 1988 advertisement that aired in the presidential primaries, turning the fortunes of George H. W. Bush around by showcasing the dangers of giving a furlough to a convicted criminal led to a fear of reducing incarceration or granting releases on parole, in ways that encouraged the reinvention of criminal incarceration as a new normal, or status quo. Neighborhoods, family members, and networks of friends share carceral experiences and stories, as well as knowledge of orange clothes, in a seismic shift of staggering proportions since the early 1990s, with few or little sufficient social services to be reintegrated into society.

An interesting statistic is mirrored in how the desire to secure our own borders, and pursue immigration offenses, as much as to police criminalized drugs, has led to an explosion of prison populations in ways that have contributed to challenges in current capacity:

One result is a major reason behind the rise of privatized prisons, no doubt, and the deep problems that they create for personal and civil rights. One hidden story of this splurge of construction–and the institutionalization of prison terms that has resulted–is, incredibly, that the rage of sentencing across the nation has created problems in accommodating and housing–or containing–future prisoners, as the practice of sentencing outstrips even the rapid rate of prison construction in several of the most prison-friendly states, including such large states as California, Ohio, and Illinois, as well as in states like Virginia and New Jersey that bear the brunt of urban criminality from nearby states or regions, with the result of an overflowing of penal institutions in many of the states that hold the largest cities:

The quite lopsided nature of the national choropleth conceals regional disparities in each state that result from a growing reliance on prisons to solve social problems or disputes of criminality or criminalized acts. But both state and federal authorities in the United States habitually displace the site of prisons from those areas where prisoners or their families dwell, and indeed to build prisons at sites geographically removed from where prisoners once dwelled. And census figures of prison populations show some disquieting imbalances in the equilibria of prison populations. One can see a markedly increased density of incarcerated African Americans in the country’s penitential system–often removed from the cities in which the prisoners originally dwelled, to be sure. With 1 in 33 black men in jail, the effects on families across the country is unthinkably severe, if not statistics that threaten to unravel the fabric of our civil society.

One can even detect in census figures a clear pattern of “forced migration” of African Americans to site of new prisons in one decade, a change presented on Prisoners of the Census but not reported in most news agencies:

A strikingly similar change in the social composition of counties that the incarceration of Latinos has created offers a similar displacement of incarcerated from their families, friends, and children–or parents, based entirely upon the construction of new correctional facilities:

What are the effects of this new populace of prisoners, and how much have national authorities taken time to consider the consequences of the real stresses on our society that result from it? One result is increasingly to divide the country, or create increasing blind alleys of bleak social narratives in select pockets of the country, which our system of imprisonment effectively marginalized from public view.

The distributions in each state of incarcerated populations are clearly concentrated in urban environments, where prison sentences seem a regular recourse of local authorities. There is a considerable clustering in specific regions in the south lands, both of those sent to form part of prison populations and parolees, if one looks at California, whose south lands seem to show a congregation of incarceration, as well as parolees. One can only wonder about the unique topographies created by the extreme density of parolees in specific areas–often around cities such as Oakland, Los Angeles, and San Diego–but extending into the interior and Imperial Valley. What sort of discussions does the clustering of returning folks on parole create within such cities and areas? What makes a spot a likely one to which parolees want to return, and to meet family members from whom they were separated from one another? What makes such separation ethically justified?

The contradictory rise of a new group of “pay-to-stay” prisons in the East Bay (and elsewhere) invites prisoners to pay an extra $155 per day to avoid being sent to the county jail facility, and rather occupy one of the Fremont facility’s 58 beds, if they can afford to do so–and suggests a tacit admission of the failure of the prison system, if not a relinquishing of state responsibility to treat inmates well. One must apply before to a judge and be screened by jail, and pay a one-time processing fee, as if joining a country club, and has led to ACLU’s criticisms of the institution of a separate “jail of the rich.”

9. Of course, the effects of the system of incarceration on local communities are widely different, if only because widespread practices of widespread incarceration are designed to marginalize communities from the nation as a whole. The concentration of prisoner re-entry into civil society in the regions around Los Angeles and pockets across the state is striking, revealing the potential proportion of prisoners and the health-risks they pose in specific areas of the state–Kern, Alameda, Los Angeles and San Diego accounting for almost half of the total number of parolees in the state.

RAND Corporation (RAND Researcher Lois Davis)

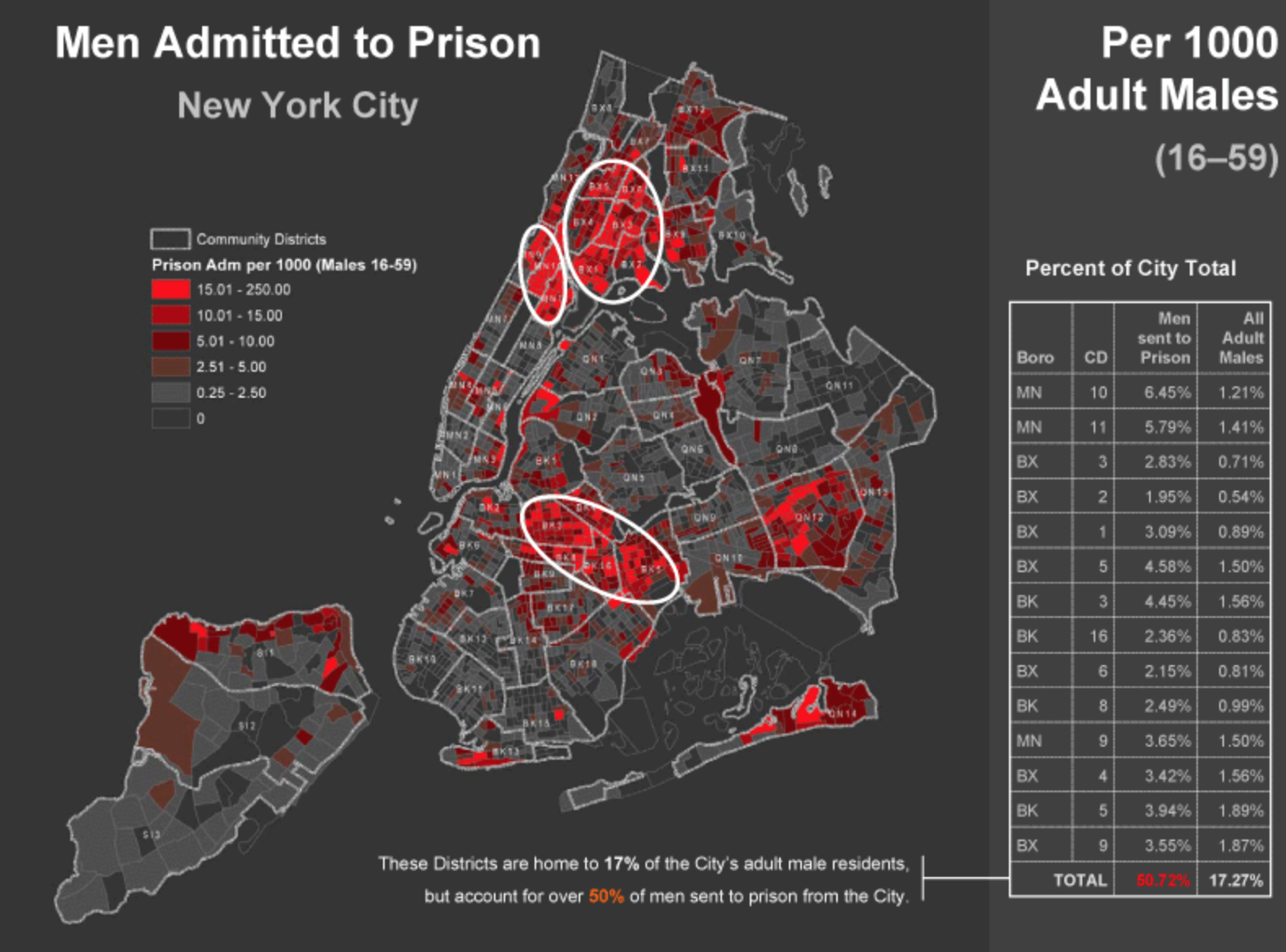

An even finer lens might be directed to the distributions of those formerly incarcerated in precise urban neighborhoods, and an outsized spending in specific neighborhoods from which a predominance of men and boys are incarcerated at considerable expense. The finely grained studies of New York City’s incarcerated provided an opportunity for the microscopic examination of the provenance of the incarcerated, and raises eyebrows of empathy about the communities from which they arrive in jails. One could go much further, of course, to delineate the disproportionate nature of urban incarceration. The staggering studies of Eric Caldera and others show the disproportionate effective cordoning off of specific urban populations in prison cells, and to muse on the map as an illustration of social costs of imprisonment. Caldera and his team have tried to correlate the costs of imprisonment with city blocks to show the way that our expenditures on prison in 2003 correlated with specific neighborhoods in Brooklyn, NY, that cast a clearer light on the distribution of imprisonment in our society.

Caldera’s aim is of course not to identify a topography of centers of criminality, so much as the lopsided nature of cultures of incarceration that become the new normal in specific areas and to specific courts. The costs to society, of course, are often extreme, given the huge costs not only to specific boroughs, but to specific regions of those boroughs.

Neighborhoods and areas which effecitvely “send” young men to prison are strikingly concentrated in just one poorer area or zone of each borough, suggesting the deeply lopsided topography of New York’s social fabric, as well as the deeply rooted cultures of incarceration where specific neighborhoods are, in essence, incarcerated, both disrupting families and making orange the new normal and incarceration a fact of daily life.

Disrupted families are a deep national cost that is impossible to calculate, and with which social services can’t hope to keep up.

This count omits those regions which palm the fees for social disturbances caused by teens onto their parents, as if to abdicate the social responsibility of the state over the underage. After kids are taken off to prison, the state does not even offer to foot the bill, suggesting the abdication of the moral, ethical, and individual consequences that a stay in the slammer might create or only intensify. The decision to abdicate responsibility for such teens–to reverse charges on the families from which they have come–seems the most ethically unjustifiable position of all: isn’t this a lawsuit waiting to happen? While parents are free to negotiate a new rate for the costs of investigations, criminal justice fees, incarceration, and even for wearing of an electronic bracelet that places the offender on GPS, accumulated criminal justice fees can allow court officials to garnish parents’ wages, claim tax refunds their parents are owed, or place liens on the parents’ property to secure fees. The Assistant District Attorney of Alameda County explains: “That’s part of being a parent; you’re responsible for your kids and their actions.” God bless San Francisco County?

Can one really conscionably place the financial blame on the families, in an age of the widespread de-funding and decline of graduation rates in public schools? The picture of those likely to face incarceration who are high-school dropouts are startling.

The statistics in this report are staggering. I feel such empathy for those families who are separated geographically; for both the children and spouse as well as the incarcerated.

I am shocked