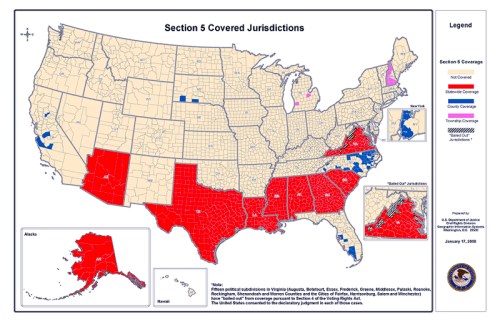

When Chief Justice John Roberts, Jr. effectively released nine southern states from the oversight of voting procures and practices in a decision overturning the Voting Rights Act of 1965, withdrawing the federal protection of populations against whom there was past discrimination and effectively judging it to no longer warrant federal review. The decision was to cease to continue such provisions of oversight–the “preclearance” of any changes in voting laws–that interfered unjustly in how states conducted their elections. Roberts most strongly objected to using maps to guide such active federal oversight of voter suppression. By rather castigating the U.S. Congress for relying continuously on historical precedent in repeated re-approval of the Voting Rights Act–or “VRA”–the five Supreme Court justices collectively complained that any continuation of policies mandating which states and local jurisdictions must “preclear” with the Justice Department when changing voting laws, suggesting that failures to “update” the “coverage formula” that was repeatedly reviewed and reinstated since 1965 no longer reflected “current conditions,” even though it had been affirmed four separate occasions by previous supreme courts.

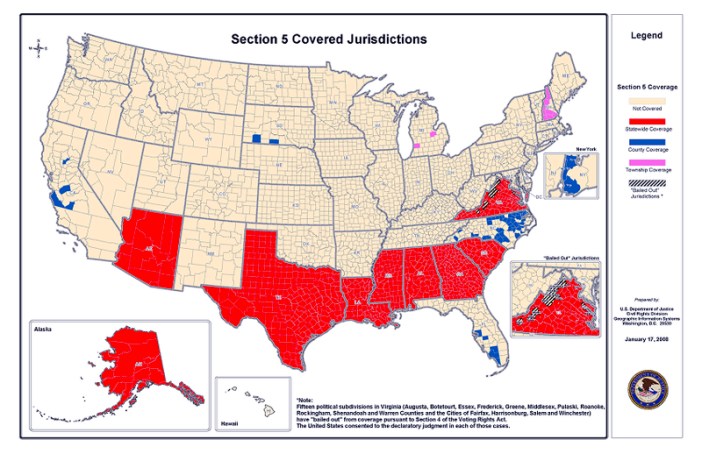

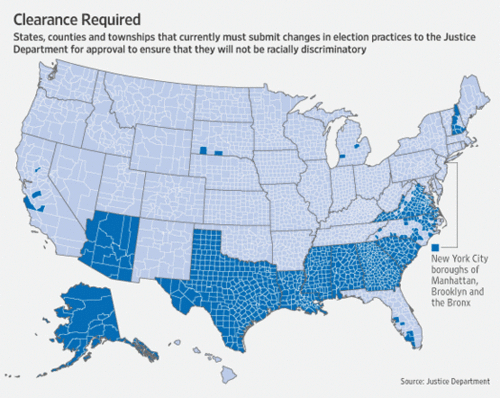

What the nature of such “conditions” were was never specified. For the actual objection of the Court seems to have lain in the unfair distribution of federal authority that the process of review of changing in voting policy created–and the degree to which it distinguished the relation of specific states to the federal government in ways that Roberts claimed he found issue. The map of those states subject to review constituted undue federal interference, it must be supposed, with state practices. Ignoring that the map mandating “preclearance” for any changes to voting laws in states had reflected the evolution of voting conditions on a county-by-county basis after having sustained a series of “incident-free” elections where no complaints were registered or found, the Roberts court seems to have treated the map as the problem in its untoward decision–viewing it not reflecting ‘current conditions’ and unfair in its isolation of said counties and states. They were less able to see a problem as lying in long-running discriminatory histories; such histories were effectively washed from the books. For the existence of such a policy, despite whatever its benefits might be, ran against the “equal sovereignty” of southern states as part of the union, despite whatever precedents of voter suppression one might find to support its continuation. Indeed, despite being broadly upheld as constitutional ad as effective on no fewer than four separate occasions by previous Supreme Courts since 1965.

How timely was the 2013 decision? In scolding the US Congress and federal government for their over-reliance on history, the court may well be accepting and instituting a blind spot in the discriminatory practices that exist in the United States, and are regularly re-inscribed in election laws–and to do so just in time for the Presidential elections of 2016.

While the Court invited Congress to take time to “draft another formula” which better reflected the “current conditions” in the country, the five justices who supported the removal of protections from the Voting Rights Act, a pillar of national voting practices, seem to have ignored the problem at hand, or its depth. For they rather petulantly subscribed to a notion of accurate mapping–the need for rendering an accurate record in a map that remained faithful to social conditions–rather than ascertain its benefits. The argument may have rested on the belief that current cartographical skills vastly outdated those of previous generations, or the belief that history is bunk.

The dangers of the 2013 decision were that they dismissed the effective value of continuing oversight where demonstrable histories of voter discrimination existed–as well as discounted he work that went into rendering a map–or what trying to ascertain what would be the lines of the new map to reflect cases of voter suppression. Perhaps they imagined that the new map could be drafted in less time than the verbal arguments were presented to the court, and that consensus would be able to be easily arrived at as to its parameters–or that any map would entail similar objections, prima facie. Although FOX news commentators ridiculed the existence of any practices of disenfranchisement in the states where oversight existed–“nobody is seriously claiming today…that there is systematic efforts on the part of the government in the south to keep people of color from voting,” stated the senior Legal Affairs analyst at Fox News, Andrew Napolitano, ignoring its value in protecting voters from facing discrimination–current restrictions on eligibility for voting in multiple states seem to have multiplied across the country like mushrooms in multiple states, preventing any serious possibility to ascertain their constitutionality in any way, and encouraging the possibility that further policies curtailing voting rights be enacted.

In a sense, the decision affirmed a strong belief in states rights, but it did so for all the wrong reasons, and in a particularly wrong-headed way. Chief Justice Robert’s longstanding reliance on constitutional written precedent encouraged him to construe the map of states requiring pre clearance in potentially quite damaging ways–and to change election laws as a stipulation that was no longer historical relevant in ways that could increase disenfranchisement and unease in electoral laws. Roberts imagined oversight as a vestige of federal interference with states rights, in need of evacuation not only since it had lost its relevance, but since vacating its authority fails struck a blow in defense of the local jurisdiction against federal interference, but he also must have known he was driving a thorn into the side of the Obama administration. While the repeal of the VRA was hailed by the alt-right as a victory of continued discrimination of whites, as if it was coextensive with Affirmative Action or insinuated the existence of undefined prejudices to what seemed a quarter to a third of the country, the fact that such preclearance reflected actual histories of voter suppression or mythical “voter fraud” in danger of recurring.

Justice Roberts did not only fail to recognize the deeply serious divides in race-based justice across the land, as has been made increasingly evident in the years since, from Ferguson MO to the nation-wide growth of Black Lives Matter; the verdict demeaned the value of protecting voters’ rights or individual access to the ballot. For Roberts objected to poorly mapping the relation of the Department of Justice to individual regions of the United States–despite their demonstrable history of discriminatory disenfranchisement–on the grounds that “current conditions” did not warrant a review of local practices of election, he effectively denied the value of such a practice, even while claiming to send the practice back to Congress: despite notoriously exclusionary practices of the recent past, the continued review of select states’ changes in electoral law lacked “rational” grounds–despite current evidence of ongoing need to protect against discriminatory efforts to reduce the most basic right of citizenship. Most importantly, the effective “map” of regions of oversight mis-stated the legal question of oversight, by allowing the plaintiffs to frame it as a division of the coherence of how states related to the federal government, rather than an alienation of the most important of all rights to protect to individuals on the ground–whose job the Court should most protect.

The replication of the map in news agencies has allowed the debate to be distanced on a map from actual circumstances of voters, orienting many to a question that seems truly unfair–“wait, the Department of Justice is only paying attention to discrimination in these states? Huh?”–rather than to interrogate the reasons why voters might benefit from such continued protection, or that undue vigilance was demanded of the once-seceded South–and indeed constituted an undue restriction on the “equal sovereignty” of southern states.

Fox News

Fox News

The suspicion that he shared for the federal government of undue oversight in local liberties however has little to do with what other members of the Court saw as the importance of protecting the universality of the right to vote. The division of states in the union that merited review of any potentially exclusionary processes of voting was recently accepted by the US Congress. But Shelby County brought suit against the state of constitutionality of the review of their voting laws in 2011, and brought the case to the Supreme Court, as a case against the Attorney General, with the argument that the federal government lacked the ability to oversee state voting laws–the “extraordinary circumstance” that warranted such a distinction on account of repeated discrimination against minority voters, Roberts held, no longer exists, or had to be renegotiated, because the map used in 1965 cannot be reasonably retained, and need to be redrawn. This seems a reasonable historicization of the map: but it threw out any need for the assessment of longstanding historical discrimination of voting rights that had disenfranchised many and institutionalized intimidation of African American voters. Weren’t such ugly histories of voter suppression come to terms with precisely because of their unconstitutionality?

Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library

Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library

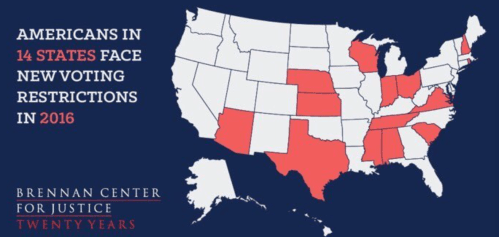

“In 1965, the States could be divided into two groups: those with a recent history of voting tests and low voter registration and turnout, and those without those characteristics,” the Chief Justice wrote in his verdict. He then proceeded to strike down key clauses of the 1965 Voting Rights Act on the grounds that the law compelled specific states to seek permission from the federal Department of Justice before changing local voting laws, and in so doing unduly compromised their sovereignty. The decision had the immediate consequence of opening the floodgates to shifting stipulations of who could vote, from the introduction of Voter ID laws to the ending of voter Registration drives, that seemed designed to –even though the actual map of oversight had been adjusted and redrawn multiple times since 1965, and the notion that an old map was being used for a question to which it was no longer relevant concealed the deep and longstanding historical survival of suspicions on the electoral voice of what were seen as minorities–and for retaining what were presented as the “local liberties” for allowing the continued suppression of the vote. It is not surprising that the rush to adopt restrictive measures in voting were adopted in time for the Presidential election of 2016, perhaps to disenfranchise the very populations seen as most egregious in forcing limitations on voters’ access to the ballot box, encouraging states to adopt restrictions on where turn-out could be potential hindered.

The judgement that Roberts so blindly and so forcefully made that “the Nation is no longer divided along those lines” which had been once determined by the discrepancies of “minority” registration and turnout provided grounds to classify Section 5 of the VRA as a historical constraint on states rights without merit because “today’s statistics tell a different story” seems in retrospect to have little merit: the readiness to introduce new restrictions on voting rights compels the issue to be revisited, perhaps in time for the approaching Presidential election, in order to ensure that full access to the ballot is not only protected but encouraged. For the occurrence of new restrictions adopted by local state legislatures suggests not only the continuing need for federal oversight–if not a strong tension between local and national policies about voting rights–but a profound misunderstanding of the lack of uniformity in how the nation will be selecting its President, not only possibly privileging the voices of citizens, but effectively diluting the national electorate in untoward ways. Although the language of the verdict refused to treat the sovereignty of different states in different manner–evoking earlier arguments of states’ rights–the notion that all states are equal in all ways bears revisiting.

When Roberts reasoned that such review of changes in voting policies, from preregistration drives to on-site registration on Election Day, were untoward interferences in states’ rights to hold elections in the manner that they desired, did he indeed encourage the actual differences in how voters were allowed to make their voices heard? At the very least, forestalling the introduction of new restrictions until their impact is assessed, and constitutionality is reviewed–given the spate of cases in which the constitutionality of Voter ID laws has been questioned–yet the dangers that are associated with a federal trammeling of states’ rights have provoked a broad rejection of the VRA provision for federal oversight of dangerous consequences.

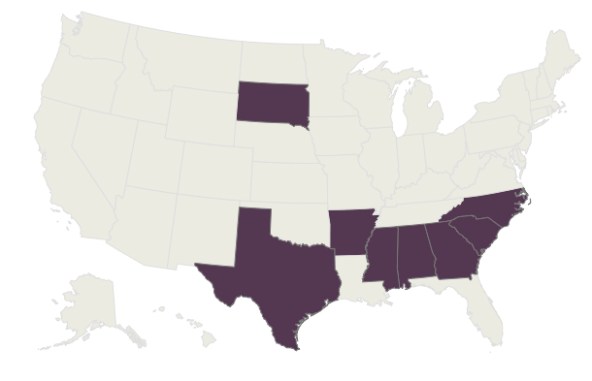

Let’s compare that with the states that were facing mandated federal oversight that was dismissed as outdated and not meriting federal review of electoral policies–not the map of 1965 but a more recent one: all but one state whose changes in voting policies were subject to oversight in Section 5 of the VRA indeed adopt changes in time for the 2016 Presidential election, but their effectiveness may impact the election.

It is difficult to grasp the lack of connection between the decision and the nation being mapped. Indeed, if Denis Wood and others has argued that national maps are a performance of national identity, the amazing nature of the agreement in 1965 to turn attention to the discriminatory practices on voter registration that existed endemically in many southern states–whose legislatures were particularly resistant to and fearful of the expansion of the franchise, and sought to adopt more voter policies that the federal government could practically review–rested in a refusal to subject states to federal oversight that was blind to race-based divisions. The decision suggests a serious blind spot about how the nation is currently being mapped. Chief Justice Roberts’s argument rested on asserting the lack of legal grounds for continued federal oversight over local communities that is unmerited at present, since extraordinary conditions now longer exist in the southern states–many of the same which fly the Confederate Flag in their capitals. The range of counties that turned to adopt restrictive policies of registration and voting in time for the Presidential election of 2016 maps (ochre) nicely onto the regions subject to review by the Dept. of Justice of any changes in electoral laws (hatched regions) and indeed the scope of restrictive policies of voting were indeed often noticeably expanded to cover and include nearby counties were large numbers of minority voters, as if the policies of reducing the electorate grew, particularly in crucial states for Presidential voting, as Florida–where the electoral benefits to the victor can even decide a Presidential election.

To stamp such a “date of expiry” on the map of vigilance to laws that exclude or encourage the exclusion of voters from an election of national consequence is not only to deny the work that went into the establishment of criteria of oversight but denies the provisional value of the map as a work in progress: the Roberts court blithely seems to seek to alter the constitution and performance of national identity, and the labor that goes into the construction of any map, while dismissing the effectiveness of that already adopted.

Chief Justice Roberts asserted that the nature of federal oversight over localities must be uniform across the nation, rather than privilege any region was effectively unduly onerous but also unfair. Rather, he urged the primacy of rigorously respecting rights of localities. But if his opinion suggested such that current practice unfairly singled out regions as in distinct need of oversight from other fifty states, and that the criteria approved in 1965–and repeatedly renewed, with some exceptions–all of sudden no longer reflected current conditions. The subsequent state of events have shown that the infringement of rights to vote both to exist in areas where the body politic still suffers from exclusionary practices that have survived in new guise, and sadly permits the encoding of racist practices and dogma in new language in existing voting laws.

Yet it raises questions of what sufficient conditions would be, and why there might not be broader oversight over election laws on a federal level at a time when restrictions on voting rights are actually being introduced. The Roberts verdict oddly comes on the heals many of the criticisms Republican candidates had only recently expressed about longstanding need to eradicate voter fraud. But rather than address the needs to reform elections or election law, Roberts argued for the compelling need to remove obstructions of self-determination that had been previously determined on a map of those states sharing past precedents of systematically curtailing universal voting. For Roberts recognized that policies of pre-clearance had stood “for half a century [as] the most effective protection of minority voting rights“–finding that given distinctions between federal attention to local practices, federal pre-clearance of changes in local election laws constituted unwarranted distinction among the states in the union–despite the clear grounds for concerns in southern states.

If the purported aim of the verdict was to ensure all Americans retained the same voting rights, opening the door to pending changes in electoral law was the basis by which Shelby County was eager to bring suit against the government led the court to take its eyes of the nation. For while determining that the extraordinary grounds for previously constructing a map of states in need of federal oversight unfairly distinguished how the Department of Justice related to states, as if the review were due only to an extraordinary condition now in remission, it ignored the issue at stake. By inviting the federal government to rely on a more current map the justices seem to have accepted the ease of redrawing a new map in the age of infographics and data visualizations that are produced nightly for the news–as if that process could be accomplished in time for the next Presidential election in a way that could be given binding fource. The justices on the Supreme Court may have lacked authority to mandate the construction of such a new map of national voting policy or the competency to do so–but in dispensing with any guidelines for oversight, they willfully opened a conundrum which they must have understood. The particular derision with which the late Antonin Scalia publicly discussed the “Voting Rights Act”–asking who would ever want to tamper or get rid of a piece of legislation with such a nice-sounding name–reveals either a misguided failure to appreciate its benefits, or past need, or the historically embedded nature of many counties’ voting laws–as was soon revealed in the institution of a range of restrictive policies of voting apparently aimed at curtailing voting rights, if cunningly cast in protecting the rights of those who had already registered. The refusal to retain a map that ostensibly “was biased” against whites was a stroke of genius for a group of white southerners in a minority-majority nation, and also came with clear political pay-off for the Republican party, as those dissuaded from voting would most likely not vote Republican.

Why weren’t the continuation of a danger of disenfranchisement evident to all members of the Court?

The cross-generational continuity believing that provisions of literacy, English literacy, or indeed the predominance of continued violations of voting rights threaten to dissuade participation in the election, and indeed increase the feelings of distrust in members of the electorate. The very existence of problems of restrictive policies about voting mandate the importance of keeping expanded locations of registration open, opening the ability of those who haven’t voted to vote, and renewing registration until the last minute. And despite the introduction of legislation to restore the VRA in the US Senate, the reluctance of Republicans to endorse such legislation reveals the bizarre transformation of the debate to guarantee the franchise along party lines–in ways that echo the terrifying vocalization by Donald Trump of charges that illegal immigrants he would not permit in the country would be accepted en masse to tilt the vote, and his attempts to undermine the legitimacy of an outcome to the election that did not affirm his victory. Such bullying of the American electorate of course itself hinders and disrespects the electoral process. For in dismissing the previous map for areas worthy of federal attention to undue limitations on civil rights, Roberts sided with a longstanding argument first framed during Reconstruction, but examined Southern claims to autonomy as undue interference in states’ rights. Yet the argument that geographical restrictions of federal oversight were no longer warranted depended on an imagined equality due all states, and a willful neglect of the map of local disparities in how voters are allowed equal access to the polls.

1. The map became what he tilted his sword against in the opinion that he wrote, leaving Justice Ginsburg somewhat dumbfounded at its limited reading of the law: the VRA did not mandate a permanent division among states, but the law specified redrawing of a map over time should disenfranchisement be found to no longer occur–in which case it would expire in regions where such oversight was deemed no longer necessary.

So how could the map be effectively fetishized as grounds for legal objection to the oversight of regions where voting practices had not yet gained a respectable track record for respecting the civil rights of all voters? In granting the petition of an Alabama county in Shelby County v. Holder, No. 12-96, the court placed the Voting Rights Act in its sights in ways that it had sought to do for some time. Roberts argued that maps of past discrimination bear little “rational relationship” raise questions of the rational relation of a map of oversight to the law–or whether a map of legal oversight can be warranted in light of histories of racial discrimination. The verdict raises questions of knowing when a new map should be required of regions that have demonstrated histories of disenfranchisement, when a map becomes overly dated in the eyes of the law–and, given how long Congress had labored to determine how the geographic limits specified in the Voting Rights Act could shift over time, when a new map would ever be collated and compiled. Oddly, the decision seems to deny a clear perception of the lack of equal access in the last presidential election–and Mitt Romney’s decision attribute his defeat at the feet of the promise of Universal Health Care (“Obamacare’) held to minority voters. In an age when a Presidential candidate can explain his failure to gain votes among minority voters on “the gifts” promised by his opponents to African-Americans and Latinos, dividing the electorate along racial lines, such distinctions clearly exist: yet Roberts questions the limited effectiveness of mapping specific states as sites of disenfranchisement as unfairly privileging DOJ oversight of select states.

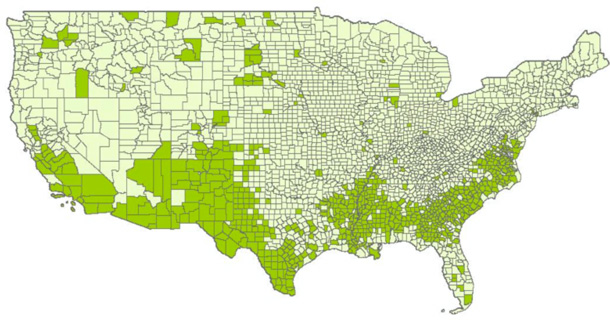

Does a map of regions requiring federal preclearance divide our national territory, in short, or is it by necessity a necessary tool for preserving equal access to the ballot across our nation? What map would be sufficiently authoritative for Congress to draw up, for one? Do the maps of discrimination retain validity on preventative grounds, or must they be actually demonstrated? If the latter is the case, who is doing the counting and reporting the results? Is it of any importance that the historical preponderance of complaints about voting laws within the United States as a whole from 1957 to 2006 closely reflect a distribution that would expand the mandate the continuation of a similar map–but include the very same regions as sites historically in need of federal oversight of election laws?

Voting Complaints Voiced at County Level in the Lower Forty-Eight, 1957-2000

Unsurprisingly, this map would reflect many of the same counties where the voting group was likely to be one fifth “minority” voters in 2000, where those attitudes against groups defined as “minorities”–Latinos or African American, usually–were sharpest and most likely to be excluded from voting.

Counties with 20% Minority Residence

Given the Chief Justice opinion that violations of voting rights “should not be too easy to prove since they provide a basis for the most intrusive interference imaginable,” and must be rooted in the explicitly stated intent to disenfranchise, Roberts would probably question the ability to map a history of discrimination at all, of course. Given that Roberts openly doubted “Congress can impose this disparate treatment [of states] forever” in oral arguments to a 2009 challenge of Section 5 of the VRA, he might well have recused himself from considering the case, but seems to have been eager to provide a precedent for explaining why the undue interference of the Department of Justice over local procedures and warranted a continued need to mandate states to request federal permission for changing election practices. In arguing for the antiquated nature of mapping a division among the states in the eyes of the law, Roberts questioned criteria for selecting the procedures of voting and elections in specific states, mostly located in the South, under the supervision of the Department of Justice: strictures on select states created undue divisions in a nation, he argued, dismissing the need for such oversight as a thing of the past–even while praising the benefits it brought their residents. Yet maps are difficult to move to a discourse of legal reasoning, and a map of discriminatory practices is bound to be approximate and selective, rather than uniformly divide the national space:

2. The 1969 Voting Rights Act introduced to rectify widespread blatant discrimination against the voting rights of African Americans, common in obstructing registration, mapped those regions where clearance was required to change election laws or voting practices. The above map continued to provide an avenue of legal recourse for minorities who faced any practice or intent of disenfranchisement. The passage of the original Act responded to registration discrepancies in 1965, but its expansion in 1975 covered a range of other subterfuges and nefarious tactics to reach the same ends–most recently, these have expanded to include from restricted polling hours to the introduction of Voter ID’s. The Chief Justice argued whatever the potential benefits of federal oversight, the distinction that the VRA drew in its placement of nine states under oversight created a harmful divide in the harmony of the Union of states, independent of the realities of disenfranchisement. He hence found lack of a compelling reason to require only nine states to obtain federal approval to alter any existing election laws. In clothing his argument in a federalist claim to state equality, Robert’s opinion raises the question as to whether mapping practices that obstruct voting provide an instrument to monitor the insidious but present evil of disenfranchisement or rather serve to divide states’ rights. For even if the metric of voter registration differences seems outdated to map distinct regions worthy of oversight, continued tactics of disenfranchisement–often achieved by redrawing maps of districting–both suggest that the drawing of lines on maps of political representation demand federal oversight.

How can one map a compelling need to supervise voting rights? Roberts might well have asked. By appealing to the uniformity of standards among states as a guiding rational of his decision, or couching his argument as a “division” of the nation, the Chief Justice invokes the lack of grounds to divide how space is abstracted in a map to strike down civil protections for voters, ostensibly to maintain equality among the states, but to restore the lack of interference of federal government in regional elections–despite the increasing hostility showed to the growing presence at polls of formerly minority groups. Many objections to the Act question its viability as a question of “racial entitlements,” as did Justice Scalia, who described the emergence of “black districts [facilitated] by law” in the House in argument. But the 14th amendment were less central to the decision than the rationale for renewing oversight of election laws in the fifth clause of the VRA, now on the books for over 40 years, and long a target of Chief Justice Robert’s ire because of the federal oversight it allows, and invites Congress to draw a new map of those “jurisdictions to be singled out on a basis that makes sense in the light of current conditions.” The Roberts court oddly departs here from an argument based on precedent, to pose a federalist argument against singling out individual jurisdictions that are in need of supervision–notwithstanding documented attempts of disenfranchisement in these regions. For Roberts, the map has “no logical relationship to the present day”: things have changed, Chief Justice Roberts tells us now; we no longer need to supervise obstacles in voting laws in select states. Yet do maps ever have such transparently logical relations to ideas or principles?

3. Maps drawn as tools for determining effective political representation are improperly treated as if they defined entities. And to argue that the map is simply a division of the polity into separate entities–as Roberts’ decision–obscures the extent to which the purely precautionary nature of review exists to ensure political representation. Robert’s argument seems to make a categorical confusion between the ways that maps abstract a record of lived experience of disenfranchisement to a region and the abstract categories of rights in legal thought.

The objections of the Dept. of Justice to ‘pre-clearance’ have in fact radically declined since 1965, but this does not undermine the validity of Congressional attempts to map disenfranchisement in the US.

Yet the map is not a territory–or a means of conjuring an entity–so much as a tool of oversight. The Voting Rights Act frames a legal avenue for redressing discrimination at the polls or in redistricting–and redressing a level of discrimination not effectively able to be monitored by pursuing suits of local jurisdictions. Roberts’ opinion withdrew the existing avenue to appeal such insidious discrimination by finding it to violate the uniformity of a map in which all states–if not all voters–were to be treated as equal. All law is based on abstractions, but his reliance on the abstract autonomy of the state is an odd substitution or sleight of hand, that preserves the autonomy of states’ jurisdictions for the rights of their inhabitants: it appeals to the abstraction of the state to question the logic of distributing persistent inequalities , rather than the injustices to specific residents of the states.

In a decision that almost mocks the intent to seek to find distinguish discrepancies in voter registration on a map by sharp divides, Chief Justice Roberts condemned the VRA as a flawed in its attempt to make reality correspond to a map of actual discrimination, and notes that the divisions it maps no longer reflects actual circumstance. This denies the flexibility that the Act has long had. The application of the law was not applied only to states, but to jurisdictions with a history of voter discrimination in any form. Yet Roberts finds that its criteria, although based on alleviating restrictions on voters, imposed unequal burdens on states’ administration of elections, as if the autonomy of states unified in the map be preserved in the face of history, and the government be protected from meddling with how the fifty states map their own representation or internal affairs–even when the outcome is in the nation’s collective interest.

Roberts’ allegation that how the VRA maps “pre-clearance” disrupts the integrity of states distracts from the actual inequality–manifested in inequality and disenfranchisement–by positing a need for equality among the fifty states. Yet, as many observers have noted, the increased anxiety at an increased number of minority and Latino voters in central and western states might make this the most dangerous time to shrink the map of where impediments to the “any voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure . . . [deemed intended] to deny or abridge the right of any United States citizen to vote on account of race or color.” Although these terms written in 1965 echo those in the US Constitution, the Chief Justice seems to find a basis to question the assertion by a rosy-hued map of uniform states rights, as if each state best flourishes when left to practice its own electoral practices no matter what practices or means of impeding a broad vote might be a direct result or consequence of them.

Roberts the strict constructionist seems to question the accuracy of a map of “covered jurisdictions” in need of judicial “preclearance” both as an impediment to states’ rights because it maps a divide he argues no longer reflects “current conditions.” Yet isn’t a map simply a convenience to create grounds for adequate representation? While finding the map of covered jurisdictions “out of date,” but accepting a map of all fifty states, he finds the previously sanctioned formula for “pre-clearance” “unconstitutional.” In the name of the specious argument of “states rights,” he seems to have vitiated the compelling nature of an argument to ensure the votes of all.

4. Roberts interpreted the individuation of nine states by historical attempts of disfranchisement as “dividing” the nation. And since these states are no longer defined in a similar manner by policies of explicit segregation of registration or voting, despite clear inequalities in the history of the regional reception of voters’ inalienable rights to vote, the majority opinion took voter registration and turnout numbers as an index of voter discrimination. Through such a metric, Roberts questioned whether such discrimination continues, or continued in such a clearly mapped manner as he grants it clearly did in 1965. The VRA defined those states it mandated to seek federal permission prior to altering electoral laws or voting practices to identify those places with voter turnout or registration of minorities below fifty percent, and hence in need of oversight to rectify deep imbalances. The seven states were subsequently augmented to include those where a percentage of voting age citizens spoke only a non-English language–Texas, Arizona, Alaska–as they were judged in need of “preclearance oversight” as well since the Act’s historic passage in 1965–suggesting th flexibility with which the VRA was long employed to ensure the equality of voting rights.

Roberts found the divided national map to perpetuate antiquated divisions that “divided into two groups” a unified country. But the flexibility of how oversight was framed in the map historically varied in response to demonstrated need, as shown in the maps of oversight compiled in the New York Times, which traced the coverage of states by the Act, coloring those covered since 1965 in deep purple, and those added in the 1970s in violet, and subsequently judged free from such voting discrimination in tan: the disparate nature of these regions suggests attention to areas in the country where electoral laws merited continued scrutiny by relatively current criteria.

The shifting landscape negotiated evidence of voter discrimination, rather than disrupting national harmony.

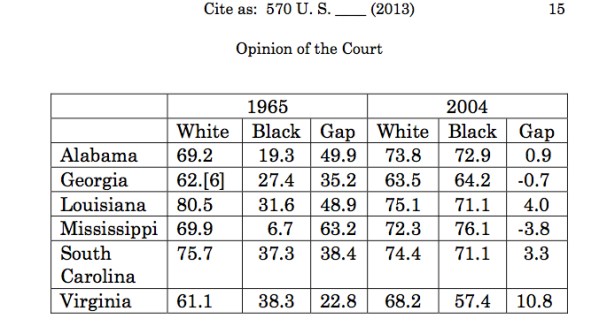

Chief Justice Roberts’ opinion foregrounded data compiled for Congress’ 2006 review of the Act to call into question the relevance with which the VRA maps a uniform division of states Congress kept under coverage. Yet in citing only one metric–discrepancies in voter registration, the original criteria used in 1965–he oddly adopts an antiquated sense of the relevance of mapping in relation to the VRA, throwing out the map on the basis of its antiquated measurement of obstructing universal suffrage, and opening the door to the introduction of further abuses by removing oversight entirely. Even while calling for basing such oversight on more current data, he avoided looking at the data that was available–summarized in part in Justice Ginsburg’s impassioned eloquent dissent–by confusing one map with the ends of oversight. And so a declining registration gap served as grounds to question the need for the continued federal oversight:

Several of the gaps in these six states survive, and the gap of registration among African American voters has been dramatically reduced in Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and Louisiana, which partly reflects the standard set by the Act, but these numbers present only a very partial or selective picture, and a map that does not conform to voting practices.

5. Yet the assiduousness with which attempts to reduce voter turnout have been since developed in many states listed above in the rise of increased minority voting, and indeed with the rise of the proportion of ‘minorities’ among registered voters. The lack of uniformity that Roberts finds in the ability of mapping disenfranchisement among those states who were mandated to submit any electoral alterations for “pre-clearance” by the Department of Justice perversely became his basis for arguing that the concept of preclearance should be jettisoned as unconstitutional in the undue constraints it imposed on nine named states–as if the question was the ability to map discrimination, or use a map to regulate voting practices, rather than its continued existence to remedy historical prejudice. So whereas the Voting Rights Act was persuasively linked to the region placed under federal coverage–or “pre-clearance”–of any changes or modifications to electoral laws or procedure, Roberts ruled that the geographic divide in disenfranchisement that was relevant in 1965 was no longer operative or commensurate with actual historical experience or current data–although the measure he chose to highlight does not conclusively demonstrate this assertion to in fact be the case at all.

But rather than look more deeply at actual data, Chief Justice Roberts appeals to the “fundamental principles of equal sovereignty” among states and record of national unity as if it were abstractly represented on a map, rather than something that played out in lived experience and effective political representation. The opinion seems partly in the question of trusting an earlier mapping of disenfranchisement. It ignores the extent to which the Act aims to prevent disenfranchisement; it displaces these questions by those concerning the propriety of mapping out a division in jurisdictions, as if to implying that uniform disenfranchisement was the target of the laws more than its inherently undemocratic evil that disrupted the legal equality of the state in the eyes of federal law, before which all states should have equality.

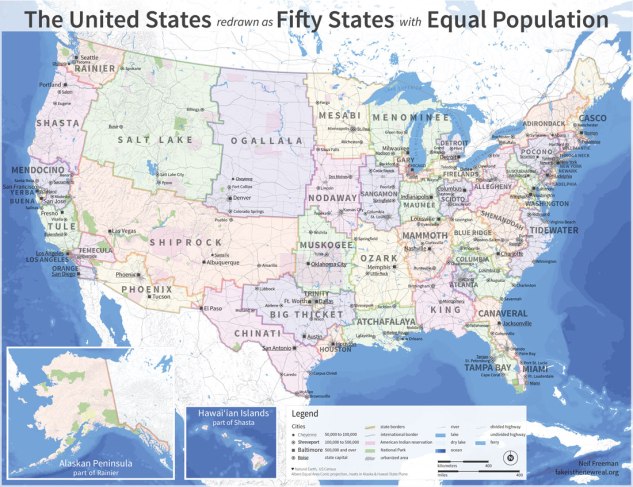

Yet are all states equal in their entitlement to police their own voting rights? Recent cartographical endeavors to draw maps of political representation by equally distributed units of population reveal that the boundaries of states are approximate realities, rather than the abstract entities Roberts accuses the framers of the VRA of positing. To distribute population were equally divided to correspond to the shifts in population in the nation, Neil Freeman decided to remap the states to allow chambers of Congress to remedy the disproportionate influence of specific states and prevent gerrymandering.

Freeman’s counter-map reminds us of the political convenience of such abstract entities, and the incoherence of some of our states as entities. It reveals the poor approximation that the existing divisions of states gives voters in the nation, effectively privileging votes of residents in the more thinly populated prospective regions of “Salt Lake,” “Ozark,” “Shiprock” or “Ogallala.”

Can the division of federal oversight be understood as an approximate and imperfect but necessary tool analogous to that of the electoral college? Such abstractions are imperfect tools for considering local electoral practices, but are the units that exist as units of electoral law, rather than as legal abstractions whose jurisdictions are in need of projection. Indeed, these convenient units for political administration poorly reflect population density–in fact, the limited density of the area of federal oversight seems less densely inhabited, and more isolated from broader cultural norms.

6. The Voting Rights Act served as a preventative that decreased a marked discrepancy among the registration of whites and minorities in these states. Yet in gutting its enforcement, Roberts found poor logic in arguments that preclearance has itself diminished potential electoral abuse, asserting it impossible to prove with rigor this as the case, and noting this lack of rationality contrasts to the undue “burdens” that the division creates.

The Chief Justice may have effectively distorted the question in an optic of states rights. But this argument seems anything but rational or watertight, with 81 percent of the voter discrimination complaints of voting practice lay in the areas where the VRA sustained “preclearance” of changes and/or modifications in voting law or elections–the region of the states who lost or settled the largest number of cases in favor of minority voters between 1982-2005, as Judge David S. Tatel had noted in the appeals court’s decision, if one focusses on those regions that lost 6 or 7 cases per million people.

This map of the settlement of cases that violated Section 2 of the VRA might, Chief Justice Roberts could object, fail to map in identical fashion onto the boundaries that the VRA enshrined–and the second excluding both Virginia and North Carolina, and providing little rational for the validity of the existing map of areas whose election laws merit more careful observation and protection. But this point denies the imperfect conventionality of all mapped entities–and the confusion in conflating the abstract unity of the map and experience of the jurisdictions it maps.

A map that measures at lest ten successful settlements of cases that minority voters brought of disenfranchisement in the years between 1982 and 2005 defines a similar region as worthy of oversight:

The question turns on what sort of maps best show current conditions of civil rights. But a deeper problem in Robert’s argument the difficulty to select a single map with a level of logical consistency as a record of conditions, given the selective nature of mapping: the map is not the territory, but construes it. To object to the divisions a map creates misunderstands its instrumentality.

Roberts found “Today the Nation is no longer divided along those lines” revealed by low registration and turnout, and finds little rational by which the division should be preserved since “today’s statistics tell a different story.” The story Justice Ginsburg offers for “the completion of impressive gains thus far made” as a way “to combat voting discrimination where other remedies have been tried and failed” against “‘the blight of racial discrimination in voting'” to give, as Oliver Wendell Holmes argued in 1903, “relief from [that] great political wrong.” The curbing of such a wrong perpetuated either by a state or its residents was the aim of the VRA, and the benefits were directly attributed to its reauthorization in 2006.

But Roberts seems to argue from the map that the unity of law is disrupted by the federal imposition of different norms. This despite fears of active “redrawing of legislative districts” to dilute the rising power of minority votes, that effectively segregate the distribution of minority votes by lines of race, drawing distinctions designed to minimize the effects of those votes, independent of registration or attendance at the polls that actively diminish the increases of minority representation: Congress found many “second-generation barriers” arising in different forms which demonstrated “the need for continued Federal oversight” in these specific regions, Congress determined, and included among other things the purging of voter rolls of minority voters; dual voter-registration schema; restricting of early voting practices or curbing late voting; openly expressed fears of African-American turnout increasing; and intentional redistricting designed to eliminate those districts where minorities were majorities–a practice noted in Shelby County itself as recently as 2008. The act, Justice Ginsburg argued in her forceful eloquent dissent, might be retained “[in those] jurisdictions as to which its application does not transgress constitutional limits.”

7. It is accepted that maps of oversight are in fact instrumental tools of political representation. Abigail Thernstrom of the American Enterprise Institute has written pointedly that the primary reason for defending Section Five of the VRA is to secure African-American constituencies in “racially tailored districts” that protect minority seats; she sustains the abuse of Section 5 by a Department of Justice to block Voter ID laws that would have the effect of limiting the voting franchise. And instead of protecting against disenfranchisement, the law’s current form has provided a basis for preventing “multiracial coalitions,” Thernstrom argues, and effectively continue to limit the focus of African-American politicians–with polarizing results. Yet the rise of minority voting blocks has also provided regions which stubbornly tend to support Democratic candidates, making redistricting a partisan issue. In other words, the law undermines our polity–never mind its accuracy.

The redrawing of electoral maps in response to Roberts’ ruling so that they minimize minority votes is an inevitable irony of Roberts’ failure to see any reason to map of federal oversight on specific states. Within two hours after the public announcement of the Supreme Court decision–in a move either premeditated or revealing insider pre-knowledge of the decision to come–when Texas’ Attorney General Greg Abbott announced the return of voided voter-ID legislation designed to curb minority voting together with a new redistricting map limiting Hispanic and African American voters–both previously blocked as discriminatory, unveiling a new map of the map of Congressional districts in the state that effectively minimized the impact of a growing number of Latino votes in ways that are not revealed in the limited metric of registration. In fact, Abbott could barely contain his glee, tweeting to the world “Eric Holder can no longer deny #VoterID in #Texas after today’s #SCOTUS decision.”

The redistricting in no small part responded to the growth of minority voters in the 2012 election, designed to restrict the effects of district demographics–it can be viewed in clickable form here–that responds to the recent dramatic rise in non-white voters in the state.

Both changes had been earlier blocked by the Department of Justice for targeting growing minority communities in the state of Texas, by passing the most stringent Voter ID laws in the United states. Critics of the map–“drawn in secret by white Republican representatives, without notifying their black and latino peers,” according to Aviva Shen,” or Voter ID, argued that it would effectively diminish minority votes. Local resident Mack Green observed ruefully, “Travis county looks like something drawn by 5 malevolent and blindfolded pre-schoolers. . . . . Gosh, can this be the rampant voter fraud Republicans are fighting to prevent?” Unsurprisingly, a range of states are collectively moving to re-adopt previously banned Voter ID laws, in ways that promise to change the electoral map: Attorney Generals in Alabama, Arizona, South Dakota, and South Carolina all want to institute Voter ID laws that they argued the Voting Rights Act impeded. Is this related to the election of President Obama with huge majorities of African-American, Asian-American, and Hispanics, but less than half of white votes? Ari Berman questioned the relation to recent controversies around past evidence of voter suppression: “There’s a particular irony to the Court killing Section 5 just months after a presidential election in which voter suppression attempts played a starring role.”

The map of voting rights will in the coming months quickly be redrawn elsewhere in response to the court’s short-sighted decision to remove preclearance across nine states. It is ironic that Chief Justice Roberts’ argument began from the imposition of an unfair division of the map that the federal oversight had first created. One can only hope that “dignity” will re-emerge as a standard by which to enforce a redrawn region of oversight.

Splendid use of maps here! Amazingly quickly done, too!

Pingback: To Levitate an Elephant | Musings on Maps