In the shadow of two large, formerly centralized states–Iraq and Syria–the “Islamic State” has spread across their common confines in ways that seem to re-map the Middle East. The surprising success of the ISIS in Syria has been striking in the face of fatigued fighters of the Free Syrian Army, who, exhausted by fighting three years after the uprising began, have enjoyed considerable success in the face of the attrition of rebel fighters. Even as the Assad government worked to retake significant ground in the country’s center and north, the new stability of ISIS has drawn on Sunni ties and allegiances deeper than national ties, and promised greater regularity in food supplies that have enjoyed wide appeal in a worn-torn country.

How to map the basis of this appeal, and how to chart the entity of the Islamic State has frustrated western cartographers and news maps alike, despite the proliferation of maps to track the unfolding of day-to-day events on the ground. Recently, the possibility that “it may be too late to keep it as a whole Syria” that John Kerry acknowledged–and that the prospect of dividing the country between forces controlled by and loyal to Bashar al-Assad in Syria’s northwest–would be a painful rejection of a secular Syria. It would also be a capitulation of sorts to Russian interests of securing a rump state of Syria to defend their airbases and deepwater naval bases in Tartus, established since 1971, confirmed by the cancellation of a huge $13.4 billion debt for Soviet-era arms sales in 2005 of which Russia is loathe to abandon as it is the basis for continuing arms sales and its sole tie to the Mediterranean. The capitulation to the division would effectively abandon parts of the country to the Islamic State, Hussein Ibish has argued, as a “Little Syria” would effectively be a Russian client state, and a strong ally of Iran. The current plan for partition seems to take its spin from the Russian demands for a sphere of influence, but would carve Syria in ways that erase the state. A cartographical archeology reveals the deep difficulties in preserving the current theoretical national boundaries of the multi-ethnic state.

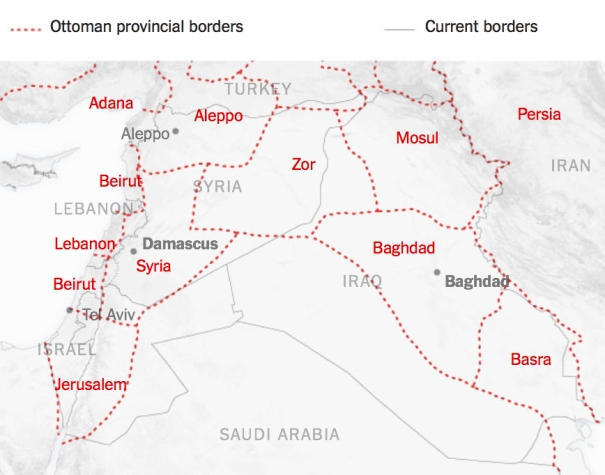

The boundaries between Syria and Iraq drawn for the interests of occupying British and French powers at the end of World War I and fall of the Ottoman Empire at the Sykes-Picot Accord of in 1916, is being altered in the region’s current map: yet the deep destabilization created across the former provincial regions of the Ottoman empire reflect problems in defining allegiances in a map. The increasingly tenuous ties across the region are tied as often to the provision of bread or the guarantee of temporary security in regions which have suffered ongoing lack of stability in past years–or any ties of food or health security–as they are to the effective tolerance of an ongoing civil war that has destroyed national infrastructures. The severe instability across Syria that has ramped up support of ISIL, making the Islamic State a credible opposition to Bashar al-Assad, that reflect less the undue carving of the Ottoman Empire’s expanse than continued juggling of a system of alliances to secure oil, with little attention to the country’s inhabitants, that have allowed us to tolerate or suspend attention to the deep instabilities revealed in Syria’s civil war, and to the effective implosion of its state.

The newly centralized state that has emerged after the truncation of its name from the “Islamic State of Syria and the Levant” to “ISIS” transcends the notion of national boundaries. As much as reject the reconfiguration about the littoral region of the Levant, in pivoting from the Mediterranean region of the Levant, ISIS has tried to assume the status of a state that is able to recuperate the notion of a mythic caliphate as a point of resistance. But it is deeply rooted in the Syrian revolution, and a good portion of ISIS fighters have not only come from Syria, but have left the Syrian Free Army for ISIS, a more credible opposition to Assad’s regime, dissatisfied with their own leaders, and attracted by the clear vision of a state that the Islamic State provides. The declaration of a New Caliphate not only “seeks to redraw the map of the Middle East, but dismantle the shortcomings and maladministration that is associated by earlier mappings of the region, and with the corruption of the Syrian state.

Its future survival however raises questions what sort of unity and coherence exists within a region out of the deep instability of Syria’s civil wars. There is a clear tension in articulating a “State” in dialogue with extant maps, including the many maps drawn and redrawn across the region since World War I, in the hope of securing more fixed territorial bounds than existed in the Ottoman Empire, and a rejection of the territorial entities that seem to have been created in a colonial past for the ends of replicating a Eurocentric balance of powers, as much as the needs or allegiance of local residents. Although ISIS promises to promote “justice and human dignity” for Muslims everywhere, the creation of such universal claims to over-write existing formerly centralized states in the region–dismantling any pretense of unity or national centralization that used to exist in Iraq, or of the imploded state of Syria–only mask a deep fracturing as individual oil companies back the break-up of oil-rich northern regions of the former Iraq in ways that may yet happen in other regions of the Middle East.

Regional stability seems likely determined less by either e arrogant declarations of territorial rights or local self-determination, sadly, than the outside support that new regions can muster to support their coherence in a badly destabilized region. It is impossible to map as a political entity, or without taking account of the recent destabilization across the Middle East, and the implosion of Syria’s civil society as its leader, Bashar al-Assad, has clung to his role as titular leader. Indeed, it was within the Syrian civil war’s destabilization that the organization of ISIS first emerged as a way to reject Assad, first in the far northern city of Aleppo and Raqqa, among other rebel groups, but that has grown into the Islamic State. The foundation of an Islamic state was far removed from the goal of the Syrian Free Army or other rebel groups: after being ejected from the Free Army this past January 2014, the group moved east along Syrian’s borders, seizing towns and capturing money and munitions with the aim of remapping the former state of Syria and crossing the Iraq-Syria border, to achieve a new Islamic state, and expanding into the Anbar province and oil-rich zones of northern Iraq, the region controlled by the “Islamic State” has created a conundrum for cartographers as it breaks from existing national boundary lines, and depends on decidedly post-national allegiance. Even as the current fracturing of Iraq into sectarian regions backed by different sources, post-national maps of the region depend on the reconciliation of the arrogance of ISIS in staking claim to possess the region by natural right in near-Iliadic violence with attempts to meet the limited resources or scarcity and deep destabilization on the ground that has been increasingly attempted to be mapped–but whose deep underlying causes remain difficult to represent adequately.

* * *

What the territorial constellation of an Islamic State would be is difficult to map–as is the cartographical basis to map such a “state”, now expanding along the Euphrates toward areas around Baghdad, which has destabilized any sense of the centralized nation that once existed in the region. At the same time as selling formerly Iraqi oil to the Syrian government, and growing its command from former Iraqi prisons like Abu Ghraib, ISIS seems to rewrite the bounds of a “mappable” state, as much as to rewrite the boundaries of states in the Middle East, in ways that raise deep questions of the meaning of territoriality and territorial coherence across the region. While boundaries of an Islamic State seem destined to remain unclear for some time, the rhetoric of purification and restoration that is animating the logic of a “New Caliphate” strongly draws on rewriting on wrongly imposed boundary lines that are the vestiges of imperialism. Indeed, the new divisions forged in the landscape of a civil wars in Iraq as in Syria, whose claims for legitimacy increasingly derive not from a civil solution to a multi-ethnic cosmopolitan state, but from the invocation of a Sunni successor to Mohammed respond to a longstanding destabilization of the map across both countries which deserves to be mapped. Invoking a Sunni heritage of transcendent harmony that would void the authority of all civil states, erasing divisions in an area extending from the Mediterranean to the Gulf, responds to ongoing destabilization brought by ongoing and mutating civil war. Rarely has a state conjured up a map both with such rapidly shifting and somewhat hypothetical frontiers, and so clearly both engaged with multiple traditions of mapping, even as it rejects the notion of fixed frontiers to define its own unity across two states.

The apparent endgame or sectarian standstill have made it particularly difficult to map either the boundaries, continuity or coherence of Syria as a region. Maps of the region’s destabilization offer a point to engage with the newly announced Islamic State than any maps we might devise, for the expansion of this new Caliphate seems to lack clear frontiers as it lacks clear models of civic engagement and indeed the execution of Christians and members of other religions to an extent unimaginable in western civil society. From having seized the rebel-held city of Raqqa, now its capital, the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS) or Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) transcends the category of “Syria” in the struggle against the Assad regime–or threatens to usurp it, based on the reconstruction of a different map than has ever existed in the region. Despite the attempt to create a sense of mythic unity through their own media organization, producing compelling dramatic videos for viewing on YouTube, and calling for an Islamic State purified of other religions, and cleansed of colonial legacies, by demanding obedience to a region without bounds, the group appeals to an imagined map of the region’s unity, and indeed an imagined collectivity–unlike the Free Syrian Army or existing Syrian state–and the dismantling of the civic structure of Syria or Iraq as a nation-state.

The appeal of a broadly defined religious unity so powerful among foreigners rejects civic participation, but follows a notion of purification of an imagined state, detached from the very historical events and influences tied to threats of destabilization. It can perhaps be best mapped, indeed, by the results of destabilization in the region, as much as imagined as a continuous or uniform entity. Indeed, such a program of mapping would need to take as its primary scope the inverse of the usual objectives of maps–uniform coherence, continuity, and stability–and might do well to track instability (and acknowledge its causes) as the focus of future informational situation maps.

1. The Challenges and Limits of Recent Regional Maps

The problem seems to map “Syria” onto borders in which its citizens can believe is quite urgent. Recent American commentators tie the implosion of the Syrian government to the imposition of “false” colonial boundaries uniting multiple linguistic and ethnic groups. But such mapping of ethnic divides fails to reveal the fragility created by recent destabilization of the nation. For while Syria’s cosmopolitanism lay in its diversity, mapping “divides” of religion, language, and ethnicity only start to imagine the failure of Syria as a state. Indeed, the failure to examine the true contest on the ground in Syria continues with the sectorization of Syria as if uniting disparately fragmented ethnicities and linguistic groups, in maps that openly seem to undermine the coherence of what was long a fairly cosmopolitan collection of urban metropolises, towns, and more rural regions.

Washington Post, August 27, 2013

Washington Post, August 27, 2013

The static nature of such splintered maps provide little basis to understand local or regional unrest. Recent data visualizations better excavate the levels of instability on the ground. Given the depths of instability that continued civil war has created across Syria, maps of the Syrian conflict suggest the fragility of the region’s future as a state in ways that the “Islamic State” would undermine. This is not to say that the state is destined for dismemberment or decline, but that its unity has been systematically undermined. While the ISIS forces seek to erase the border between Syria and Iraq reached at the Sykes-Picot Accord that divided the countries’ borders to benefit European interests in securing allies in the region, the continued destabilization of the Syrian civil wars increasingly evident in recent news maps. The continued breaching of Syria’s own boundaries, and the displacement of populations within its failed state, provides tinder for the illusory harmony of the Caliphate as ending the level of violence that has already become endemic across the land.

The mapping of divisions within Syria and on its borders suggest the deep failure of the Syrian state. The Islamic Caliphate’s stated aim of undoing “the partitioning of Muslim lands by Crusader powers” resurrects a largely theocratic inheritance removed from the divisions of civil life. To be sure, the region has been multiply re-mapped since ancient Roman times. But calls for an “Islamic Caliphate” that would incarnate a unity of values and principles parallel the disintegration of Syria as a nation–which, notwithstanding the continued tenacity of Syrian strongman Bashar al-Assad, has more imploded s failed state since Assad’s deadly crackdown on the Revolution from 2011. Despite promises to step down “in a civilized manner” back in 2012, the Assad regime has only been perpetuated by an open “shadow” war between the Syrian Free Army, a government supported by Teheran, and ISIS: the extremity of his government’s violations of civil and human rights have made him one of the most wanted men in the region. Indeed, calls for Sunni unity respond to the destabilization across a region that created through the radical exacerbation (or fabrication) of increasing sectarian divides. We’re apt to see the region through the coherence it had in the Ottoman Empire–an administration undone after the close of World War One at the secretly concluded 1916 Sykes-Picot Accord that transformed three administrative regions to zones of European influence. But the resurrection of an imagined region extending from the Mediterranean to the Euphrates in the Caliphate respond to the destabilization of its coherence on multiple fronts, and seek to conjure an imagined unity across divides increasingly evident in maps.

Indeed, the results of the failure of Syria as a state from 2011 are themselves quite terrifying to map, given the huge displacement of civilians into neighboring states. The internal displacement of some 1.2 million Syrians and refugees in Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon and Turkey has created a humanitarian crisis of incalculable proportions and duration. In fact, charting maps of instability across the region would offer a better basis to track its emergence than define its boundaries in the situation maps and news maps we produce. The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria seems an impossible cartographical construction in an ongoing stalemate across Syria that is already difficult to grasp. Even as we finally have more accurate maps of the civil war’s spread across that arc around the desert lands at the Syrian interior–many of which exist thanks to the courageous Cédric Labrousse, any resolution of its divides seems only more far away. We remain unclear about the strength of the rebel forces as relations between Islamist groups and the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces, not to mention the coherence and ambitions of an entity of an “Islamic State,” but feel their presence in the creation of a new Syrian and Iraqi geography.

The imperative of mapping provides one of the few ways to retain coherence of an increasingly contentious, bitterly divided, and fragmented region. The divisions between areas held by Syria’s failed regime and the forces of rebels and ISIS troops have been as difficult to grasp, given many covert divisions. The destabilization of the region is evident in an aggregate map of civil disturbances in the Syrian conflict from 2011 to 2013, most concentrated inland of the country’s more heavily settled western coast, which presents a difficult picture of a land long divided; the useful interactive visualization from the New Scientist, which effectively illustrates widespread civil conflicts across the country as a heat-map of ongoing unrest to suggest the difficulty of mapping local allegiances or consensus–in a suitably (if rare) black base-map of the region designed to foreground such disruptions, particularly useful since it is able to be searched from 2011-13.

On the one hand, the invocation of the mythic promise of restoring a “new Caliphate” suggests an illusory harmony that would be more present on a map than on the ground. Its invocation no doubt reflects a desperate search for a “more just world” by a symbol of sacred unity, it is a hope for a more just path to modernity. How can we understand the solutions that such an invocation of a mythic state allows? When we continue to project deep ethnic divisions at the base of this strife into maps, we make it harder to stock both of the political vacuum in the region, made all the more evident with the demand to transport gas and petroleum through a region which has already been deeply destabilized.

Indeed, despite attempts to discuss the lay of the land only by noting its sectarian divides as battle lines, or the revival of sectarian hostilities in the region that are nearly as old as Islam,” the implosion of the political map of the region seems a redrawing of the territorial tensions assuaged within the former Ottoman Empire. The disintegration of the Ottoman Empire, once relegated to the history books, has however begun to haunt the endgame of Syria’s civil war with the dismantling of the boundaries defined only at the Sykes-Picot Accord of 1916 that first created the boundaries of Iraq and Syria from what was the Ottoman Empire. The below reverse-visualization reveals a sort of ‘cartographical archeology” of the Empire’s former administrative regions, imposed on the region’s current map: and if the spectre of the “militant group currently marching across Iraq” trying to seize the territory to create an Islamic state” suggests territorial ambitions, we might better map its progress in terms of the destabilization across the area.

New York Times; using drawing based on Rand McNally 1911 world atlas’ map of administrative districts of Ottoman Empire

New York Times; using drawing based on Rand McNally 1911 world atlas’ map of administrative districts of Ottoman Empire

It has become increasingly difficult to ask what sort of map might relate to a political resolution of the deep divisions that have spun out in an ongoing conflict that claimed over 150,000 lives and promises to claim many more–or, more importantly, imagine what sort of map better serve its residents. Yet it is clear that we can map the depth of the sources of instability across the regions of Syria and Iraq. The nation-states clearly don’t correspond to a tapestry of the faiths of believers, nor do divisions across the regions only respond–or constitute the precarious endgame–of timeless animosities western media read into the deep-set conflicts across the region and have often invited us to use to interpret them–and read the maps of sectarian violence.

We have only begun to be provided with accurate maps of the Syrian conflict, perhaps now made more imperative with the declaration of the “Islamic State” by ISIS, or ISIL–the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levantine. The truly terrible and horrific costs of such sectarian strife were long either difficult to note or absent from most maps of the region, even as lines of the ongoing civil war are contested, difficult to define, and hard to mark by clear lines: boundaries are blurred in even the best maps of mid-2012 and mid-2013, tagged as if by an air-brush or graffiti spray paint, reflecting an ongoing problematic mapping of a state for at least four years, as westerners puzzled at what the boundaries of that state might be.

Rather than mapping the unity or continuity within Syria in a uniform manner–for that uniformity has been lost–the mapping of Syria poses the problem of representing the nation’s future identity and unity, as well as the continued costs of ongoing statement of its civil war. The declaration of the “restoration of the caliphate” by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levantine runs in the face of how we are apt to create states on maps and use maps to frame questions of state-formation. The difficulty to map Syria–and the destruction the unity of Syria in the revolution make it increasingly difficult to envision resolving the destabilization of its ongoing civil war.

2. ISIS’s Rise and the Fragmentation of Syria’s Civil Wars

The multiple situation maps devised to depict the contested region over the past year implicitly respond to the deep question of what pathways American or foreign assistance or intervention in the region might take, at the same time as what a potential exit strategy would look like, rather than embody the group that still possesses no clearly recognized boundaries, even if it has retained its Facebook page as a terrorist group (ISIS) until June 16. The very difficulty of mapping contested boundaries now seems a sort of inevitable prelude to the declaration of an “Islamic State.” Even though the evocation of that entity has made great claims to represent all Islam, and the leader of the Caliphate of all Muslims is only rumored to have appeared in a video, filmed in Mosul’s largest mosque, with the declaration that all nearby Shia shrines had been destroyed. The raging of war has been mapped til recently as a “civil” war, within the confines of the Syrian state–whose shifting divisions are not often clear, or so clearly able to be mapped onto ethnic and spiritual divides, but are focussed on Syria’s most settled regions in the north and along the Euphrates river, although this seems to be ceasing now with the arrival of ISIS troops. Beyond Syria’s own boundaries, the illusory harmony of the Caliphate as a restoration of a lost harmony responds to the cultural and religious diversity that has been long characteristic of Syria’s cities.

The broadening of areas of military contestation, particularly along the Euphrates, is suggested in the below maps, as well as along the border with Iraq, in northern areas with Kurdish militias, and to a lesser extent on the border with Jordan, as the cities have emerged as battlefields.

Map by Evan Centanni, August 2013

Map by Evan Centanni, August 2013

Can one map destabilization by its effects? Despite the absence of horrific violence in these maps, there is a desperate attempt to register the cumulative effects of war in the synoptic maps that tally displaced persons created in the civil war in offset boxes, although they only skim the surface of the war’s disastrous effects on the regions of a divided Syria:

US Department of State, Jan 14, 2014 (Congressional Research Service report: Armed Conflict in Syria: Overview and U.S. Response)

US Department of State, Jan 14, 2014 (Congressional Research Service report: Armed Conflict in Syria: Overview and U.S. Response)

Or this declassified map of the numbers of Syrians fleeing violence of 2012:

US Department of State, Humanitarian Information Unit 13, June 13 2012

US Department of State, Humanitarian Information Unit 13, June 13 2012

An expanded detail of the unclassified 2012 map for the US Department of State reveals the strong concentrations of refugees and displaced Syrians on the recognized borders of the country, both along and near recognized crossing of international boundaries with Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan, and Iraq, which is particularly telling, but which notes the far greater number of displaced within the Syrian “state”:

The far greater regions of contention reveal a country that was, as of December 2013, not only sharply divided but some of whose largest cities–Homs and Aleppo–remained divided within themselves:

Map by Evan Centanni, December 2013

Map by Evan Centanni, December 2013

(More current maps of the region, that include the spread of the ISIS in the north of Syria and along the Euphrates, are accessible from Political Geography Now, who have tried to provide current maps of events in the region.)

A similarly striking interactive map of the deep and ongoing costs of civil war has been constructed in ongoing fashion each day, collated daily on the website Women Under Siege, in an effective depiction of endemic violence for many of Syria’s inhabitants–in live crowd-sourced mapping of violence against women and children, where all sexualized individual or group attacks committed by Syrian military against men, women, and children in the region, localized in a Google Map format, as soon as they are reported:

These costs are absent on other maps of regional division that suggest the region’s destabilization. The tactical “situation maps” that we consult condense information in easily legible formats to parse varieties of assaults and strategic battles–but omit all those attacks not so far confirmed–but presents a contemporary up-to-the-minute image of the high costs of the violence of sustained civil war. Much is always, of course, omitted from these attempts to chart the results of a terrifying civil war that has claimed untold lives and created refugee crises across the region. Even as the Syrian government seemed to have won control over a large area of the coast from Damascus to Homs, a situation map released by the BBC this March 2014, using five colors with two different shades to suggest the varied limits in government’s increased control of regions save in its East and North. (The BBC map met be a bit misleading, given the town-by-town nature of the current conflict, but suggests the difficulty of establishing any boundaries or clear frontiers in the regions.)

The divisions are often mapped in more shorthand ways. Just a bit more recently, this far more simplified map, less credibly dividing the region in coherent blocks, remind us of the remove of our own attitudes to the area, even as we discuss sending munitions to the “rebels” with greater ease–and indeed as we want to make that prospect seem credible, firm divisions between “Opposition rebels” and “Government forces” more clear, and Kurdish forces more consolidated–the “Government-held lands” in this 5-color visualization which omits the fact that most of the Syrian “Government’s” territory consists of desert land:

Such empyrean maps of course betray the more complicated situation of affiliations on the ground, if they indicate the major players involved. The eagerness to declare some sort of entity joining Anbar province with ISIS-occupied areas of Syria, recently hoisted up for public view on Wikipedia as if it were a flag, since deleted, as if it offered confirmation of a state along the regions of the Euphrates; the vision of territorial unity was far more imagined and displayed online than every existing in fact as a set of boundary lines.

The newly invented unity has now been expanded so that it fits far greater imagined parameters, as if it constituted a nation-spanning-two-borders, despite the hypothetical bounding a block of solid color; such cartographical conjuring covers over the continuing conflicts on the ground, and belies the attempt to expand across frontiers at a greater rate than ISIS seems able to sustain: the appearance of a bridging of a unity of parts of Syria and Iraq, linking the Tigris and Euphrates, risks gaining an exaggerated coherence in many on-line maps that all but obliterate sovereign distinctions by rather ineffectively superimposing it on a generic Google Maps template with absolutely no sense of local opposition or ongoing struggle:

Such cartographical sleight of hands of erasure belie the far more limited web or skein of points of revolutionary resistance, and reflects, in the bounds of this amorphous identity, the seizing of individual villages as much as a growing state-within-two-states. The danger of truncating the designation of the region to the “Islamic State”–and linking it to a new Caliphate–not only runs against the recommendations of Osama bin Laden, but concretizes the materiality of the territory in misleading ways, inflating both its stability and permanence in ways that seem misleading.

Indeed, the continuity within the surrogate “government” belies the fragmentary control over individual townships that characterize the newly proclaimed state. So much is made more evident in a map of the strongholds on July 7 2014, which suggests the limits of its occupation or territory in Syria or Iraq, although they really depend on the local allegiances of Mosul, Kirkuk, and Qaim to Abu Kamal, along the Euphrates to ISIS, as much as to rebel forces, but seems to unnecessarily conflate the two, as much as the emergence of ISIL from the Rebel forces:

The most recent–and compelling–New York Times map of the anti-state of local allegiance to ISIL casts the spread of its holdings along the Euphrates as an anti-territory, creating a conglomerate both of funding from oil monies and revenues that provide the basis for and the grounds for recent attacks and for the displacement of Kurdish and other residents in ways that have only begun to be mapped. It is far more circumscribed than the airbrushed blobs of rebel resistance of earlier situation maps, or the sectorization of the region. (And it is reflected in the strategic airstrikes and deliveries of food and supplies that the Obama administration now advocates.

from Caerus Associates/NY Times (August 7 2014)

from Caerus Associates/NY Times (August 7 2014)

The aim of “remaking a Caliphate” ISIS promotes is less directed to the merging of Syria and Iraq, or the uniting of these states, as if to hearken back to a Caliphate of worldly dimensions. In a bogus map widely circulated online, if far less precise in measurement, placing the enlarged states of “Sham” and “Iraq” at the heart of a worldly empire in this bogus map, an image of territorial expansion deriving from earlier fabrication of fascist parties is falsely attributed (and credited) to ISIS’s own creation.

Part of the shock value of this map, which has occasioned comment as it circulated in western news media, for its erasure of the names of places we knew, as it entirely erases Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Jordan, not to mention Israel, and in reclaiming the Andalus seems to impose its own world-vision on maps, in an image far more evocative and ideological than objectively construed, and widely circulated some time ago by neo-fascist parties:

Yet the projection of such propaganda suggests the deeply embedded cartographical stakes of the newly expanding Syrian civil war and ongoing instability in Iraq, by expanding the region of Khurasan as a new spectra that encroaches on all North Africa and Europe–or at least the odd intersection between the claims of the neo-fascist groups who have distributed this map, including the Syrian National Socialist Party, which rather than providing insight into “the goad of a unified #Islamic #Caliphate” respond, and the quite confused apprehension of the territory of “Islamic countries” and the demands launched by ISIS–which openly disdains all varieties of Islam that call for religious coexistence–within the destabilized situation on the ground in much of the “greater” Middle East. Indeed, if the declaration by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi goes beyond the cautionary warnings bin Laden left against rushing to the establishment of a caliphate lest one raise the specter of looming adversary for enemies, the specter of the expansive map, menacingly filled with swirling Arabic abjad seems to have circulated to stoke fear of an expanding other, in ways that may have indeed encouraged military involvement in a destabilized region, as it evoked the specter of an Islamic crusade.

The map attributes a misleading monolithic shadow-figure of the total otherness of Islam that hardly exists, and masks the fragmentation that US-backed intervention has largely created on the ground, and which now finds the religious diversity in Syria so abhorrent, and seeks to enforce a new vision of religious uniformity as its foundation, purifying a previously heterogeneous land, but less able to be mapped as a uniform color.

3. What about the Map Devised at the Sykes-Picot Accord?

At the same time that we adopt such situation maps to try to grapple with the military situation that has unfolded on the ground, the esteemed Anglo-Irish scholar Malise Ruthven recently glossed the quite prominent role one map has played in the social media of the Islamic State of Syria and the Levant–a significance Ruthann went to considerable lengths to unpack. He traced a compelling genealogy of the concerted engagement of Syria’s boundary line in a quite provocative short article some have found to give greater weight than necessary to the role of Europeans in shaping the region after World War I, based on the prominence given to the destruction of the old line of territorial division in ISIS’s increasingly skillfull use of social media to promote its cause. To be sure, ISIS has prominently celebrated the bull-dozing of the Syria-Iraq border by troops, redrawing the map imposed on the region as a way of purging the region of its colonial past, or to destroy the memory of the line established with the 1916 Sykes-Picot Accord, secretly concluded between British and French governments by the French diplomat François Georges-Picot with his British counterpart Mark Sykes after World War I:

Yet does one deny some of the autonomy of the demands to emerge as a state not existing on a map by increasing the proportions of the significance of the Sykes-Picot Accord in the minds of most jihadists?

Does this vehemence really rest on the redrawing of the Eurocentric boundaries determined at the 1916 Sykes-Picot Accord? It is something of a striking conundrum that at the same time as our news outlets increasingly rely on a profusion of detailed logistical maps to grapple with the shifting role of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant–or, in a more mysteriously evocative acronym, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria–we might be missing how Sunni forces have seized upon the symbolic destruction of a map of artificial and utopian social division by which Europeans carved up oil-rich lands along divides which never existed as abstractly neatly surveyed lines that cut across the rivers running through each region into the parsing of a near-perfect polygon.

The image of the tweeted image featuring the destruction of the boundary line is something of an advertisement of the ISIS forces to redraw the map of the Middle East, affirming, no doubt, a less secular model of the state that approximated a theocratic order in place of the abstract line that the two early twentieth-century diplomats arrived at in an attempt to paper over anxieties about the fall of the Ottoman state, and what could take its place of administering what were already recognized as oil-rich lands.

The historical Accord of 1916 was, of course, primarily intended to imagine a similarly viable construction of “buffer zones” and “spheres of influence” to replace the Ottoman regime and secure British authority, rather than to frame a national identity in ways that reflected the situation on the ground. The idea was to project a balance of power, rather than build a state, and maintain a viable status quo as seen from the eye of European powers–without much regard, in other words, for local inhabitants or populations, by carving clearly divided colored blocks:

4. Re-Examining how ISIS Re-Maps Syria

4. Re-Examining how ISIS Re-Maps Syria

The region of Syria was, as a province, divided and re-divided by colonizing powers since the Roman Empire, for whom it was an important entrepôt and shipping center, but the recent ISIS denunciation of “crusader partitions” is a response to the difficulties of imposing divisions on the territory but the increased intervention in a region whose governments don’t respond, propped up as they are by the West, to local needs. As images displayed on social media, the invocation of old maps also response to a search for newly powerful symbols to inaugurate a new era. To be sure, guilt about the Sykes-Picot Accord may be haunting the West, in ways akin a return of the repressed–and of the forgotten figures of state who negotiated these territorial divisions in the wake of World War I, short-changing their inhabitants–but also provide tools of inciting opposition and to search for new forms of government.

ISIS leaders assert they are in the process of dismantling and destroying the imposition of a false map on the region that fighters are poised to destroy. Such demonization of the colonial may in itself be a bit of a smokescreen for a call designed to mask or suppress sectarianism in the name of fighting against and repulsing a common enemy: deep tensions within competing parties are choosing a foil to rally around, it seems likely, and a lingua franca of resistance to imposed categories evident in an old map of the same region: rather than protect clearly ethnic enclaves or promise a more stable social map of the region, given the pronounced hostility that has been shown to Shia shrines and mosques, and extended to the desecration of graves, in what seems a new form of terrorism: “desecrating [the] graves of saints.” The increasing news reports of the destruction of dozens of ancient shrines of prophets revered in Islamic, Christian, and Jewish traditions in but one region controlled by ISIS and Shiite militants are an extension of its return to theocratic rule, and a deep rewriting of Iraq’s and Syria’s cultural geography, as historical cultural monuments now deemed heretical have targeted in ways that seek to rewrite the region’s landscape, from tombs to minarets.

Such widespread destruction of a historical sacred space in the region promises a clear disorientation in and usurpation of the region. In Syria alone, both the Syrian government’s forces and those of revolutionaries have engaged in the desecration or near-demolition of shrines in Aleppo, Damascus, Raqqa, Tal Maruf in northern Syria near Tel Hamis and elsewhere in the country, vandalizing Sufi shrines that Sunni scholars have long recognized as worthy of reverence, mirroring how Wahabi groups responded to the power vacuum of the Arab Spring. The destruction of graves has gained a new outlet, to be sure, on social media, as Nusra front rebels displayed on YouTube the exhumation of the thousand-year old grave of Hujr ibn Adi, a revered Shiite figure, and an attack on the shrine of Muhammad’s granddaughter, in ways that have radically further destabilized the region and its inhabitants, as has ISIS’s openly broadcast attack on shrines of Owais al-Qami and Ammar bin Yasser, an early companion of Muhammad revered both by Shia and Sunni muslims alike.

Can we get some data journalists to map the destruction of such a topography of centuries-old sites of reverence, if only as a destruction of historical memory? Such long-revered holy sites are destroyed after being attacked by Wahabi groups who week to expunge them their memory as a pagan legacy, and widely displayed to audiences on social media with destabilizing intent. The broad expansion of violence appears less the manifestation seventh-century theological debates than of how representatives of different theological sectarian stripes have been demonized by their association with foreign powers and political parties.

Calls for religious, ethnic, and national purity are in short aimed at destroying the civic space that the civil war and Syrian Free Army are fighting to preserve.

5. The Perils of Re-Mapping Syria’s Changing Space

Something closer to the destruction of the very stability of the map as a flat surface bound by clear lines seems to be occurring with the rejection of political parties and existing systems of political representation. Longstanding cross-border raids on shrines have been mobilized and ramped up both with calls to arms are relayed by social media. The desecration of Islamic shrines has blossomed to the denigration of human life. We are faced with huge problems of mapping the divisions within the region, but might do better to look at the situation on the ground. The problems of mapping what the Economist in April 2014 termed the “ebb and flow of horror” tried to capture the complexly contested struggle on the ground that approaches pitched battles of resistance between fracturing rebel forces and mutual restarts to torture and kidnap, in this complexly delineated mid-April 2014 map of the contested territory that still lies between Aleppo and Damascus, and the Golan Heights, reflecting the odd geographical situation of Syria and the plagued nature of its status quo, and suggesting little sense of potential resolution, and reminding us of the low density of population outside the Western cities and the Euphrates:

The division of Syria into an ongoing endgame only broadly maps onto the divisions between Shia and Sunni groups that have consumed the region. For Syria has become a battleground of the different political possibilities that started to play out in the “Arab Spring,” when Assad first demonized protestors as Sunni terrorists. (Assad’s inflamed rhetorical posturing no doubt led to a tabled plan to invade the Syrian state.)

The pitched positions held by opposition rebels along the Euphrates and select pockets of the country’s north, suggesting the huge cost of contested lands, and defining the distribution of the Islamic State along the rebel-held areas on the banks of the Euphrates:

But the political divisions suggest the broad manipulation of sectarian groups for political interests, exacerbated by the reliance on religious networks to create state entities not only in Shiite Iran, but the US ally Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Syria, in ways that have given new vitality to the ISIS or ISIS as an opposition group. The more current conventions adopted within the New York Times to rewrite blocks of regions as if securing enclosed fortified redoubts might be more accurate representations of the piecemeal back-and-forth that we now think of as the advance of the ISIS, and a situation on the ground where lines of control are less understood as blocks of territorial administration, but as villages that either accept–or came to doubt as occupiers, in a negotiation of apparent lesser evils. Indeed, the ongoing civil war has come down to a battle over individual villages and cities, it is clear, that have threatened to implode the very nature of Syria’s future unity:

Invoking the imposition of th e Sykes-Picot as an explanation of current events–for all the appeal of its cartographical neatness and cross-cultural misunderstandings that underpinned the deal which gave the Arabs less say over the determination of their boundary-lines–may be beside the point. It casts Syrians as actors who react to European cartographers. What effect was there in Sykes-Picot than the inscription of false boundaries of territoriality among new nation states? Previously to when Sykes-Picot inscribed these boundaries so optimistically in the land, a clear organization of the provinces that make up the current Iraq existed, but which offered greater respect to divisions of settlement as well as religious and ethnic bodies:

Indeed, calls for a “New Caliphate” on Sunni grounds conjure an illusory harmony that would be more present on a map than on the ground in somewhat romantic and somewhat desperate ways that would be a legitimate representative of the Islamic faith. The expansion of the unity of administration of the region was understood less in terms of notions of territorial possession and coherence, in this 1873 pre-WWI Arab world as a province of Syrian possession in this Arabic map, which labels the Palestinian area as the “Province of Syria” and cast the current region we associate with “Israel” as part of that Province. But the map is not an equivalent to the expansionist hopes of the current Syrian National Socialist Party: it rather uses mapping formats to create an undifferentiated waqf that freezes property rights of a privileged few in an administrative region, with only superficial resemblance to the notions of territoriality–which we are tempted (wrongly) interpret as if it possessed territorial boundaries:

But it didn’t have such territorial divisions as a waqf. Maps of course quite capably conjure imagined social bonds of unity for the West, even across a region where boundaries were perhaps far more fluidly understood, and the attribution and imposition of coherence is particularly difficult at a time when the declaration of a New Caliphate has prompted some soul-searching in social media, and not only among Middle-Eastern intellectuals and religious scholars about how and why this new entity has materialized. Regional coherence is something more akin to a speculative creation in this 1895 Rand McNally atlas, where “Syria” is prominently noted, but seems to lack clear administrative boundaries, as well as extending to the East Bank of the Dead Sea, abutting Aleppo, Palestine and Lebanon, and the cross-cultural Mesopotamia of particularly fluid bounds. But to call this administrative map a model or precedent for a divided set of sectarian regions seems too easy an alternative.

This slightly subsequent 1911 Rand McNally map of administrative divisions is difficult to read as a guideline or model for what might emerge, especially because of the sustained violence that has emerged in the region. But what, for that matter, is Syria? Although the costs of war always resist mapping, the involvement of foreigners on sectarian grounds in the country’s civil strife that make boundaries and territoriality subvert any clear mapping of the war.

The hidden motion of military materiel across boundaries have as Ban ki-Moon has recently astutely observed, escalate the military violence in the region in ways that upend any narrative of victory: as aerial bombardment of civilians continue, while others are starved, and flows of refugees grow, the massive costs of war are pushed down the road. Is this search for a map in any way able to be compared to the impact of the destruction of sovereignty or territory and regional destabilization that was accomplished in the Iraq war? Of course, a scrabble to inscribe such divisions in order to administer or effectively organize the region for exploitation and commerce emerged after World War I, with the Ottoman Empire’s demise. The image of the area could have, of course, been quite different, and were actively proposed on repeated occasions, with the promise from the English that Arabs were worthy of greater territory for joining combat against the Ottoman Empire. Multiple acts of cartographical conjuring exist:

For boundary lines know no inherent bounds in the region, and are not themselves the basis to generate its unity. As recently as 2011, the Syrian Socialist Nationalist Party evoked the expanse of Syrian lebensraum, appealing to the unity of a catalogue of ancient semitic tribes of Mesopotamia, addressing linguistic and cultural divisions in the region by defending the “organic unity” of a “greater Syria” that occupied the Fertile Crescent as one region that “blended Canaanites, Chaldeans, Arameans, Assyrians, Amorites, Hittites [sic], Metanni and Akkadians.” This oddly erudite neoclassical spin on the ancient world as bound by the Taurus and Zagros mountains around Mesopotamia is pictured below. The recent map of Syria’s Social Nationalist Party indeed enacts its own cartographical fantasia, by encompassing modern Israel in its bounds, and renaming the Mediterranean as the “Syrian Sea” that adopts a vision of the region from Damascus which oddly perpetuates the Sykes-Picot myth that all sovereign bodies are to take more modern form as territorial nation states by mapping their frontiers on clear lines, yet also to try to reconfigure the map of the Mid-East around a mythical-historical image of “Syria”–and treating the map as an explicit vehicle for national propaganda.

6. Remapping Syria?

How to even consider boundaries based on the return to a potentially endless redrawing of lines? There is currently much talk of the necessity of partition and even support for partition from Iran, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey, since the geopolitical world of post-WWI Europe is not alive, nor the Cold War détente that inherited it after WWII, in hindsight it is incredible that spheres of influence weren’t seen as perhaps just the wrong way to continue to conceptualize the region, and even buffer-zones, which tend to misunderstand the on-the-ground divisions in terms of a jigsaw puzzle of a map that isolates what we define as potential radicalism.

Especially as the considerable stakes for geopolitical control of regions of oil and gas supplies become obscured in the very mapping of ethnic or religious diversity. With increasing atrocities on the rise in Iraq, any prospects for a peaceful resolution more distant, subverted by regional violence across Iraq, the needs of refugees and people have been obfuscated–as have the different divisions of faith. And ISIS has emerged as a uniquely border-crossing state, linking both Syrian and Iraqi sides of the Euphrates and using border crossings as sites to exchange personnel, war materiel, and munitions, linking two nations separated for a century by a border line as a new entity, as well as to hold potential energy sources–like the Haditha Dam or Falluja Dam–on which so many Iraqis depend. How can one map destabilization without reverting to a map dismembered by ethnic divisions?

The re-writing of the border between two states once were constructed by Europeans is an active re-writing of the political topography of the region, to be sure, although it is difficult at this point to know how it would translate into a map, or be translated into a pragmatics of mapping. The discussion of remapping the region in ways that would respond to the tensions between groups’ relation to Islamic religion don’t bode all that well. In Iraq, it increasingly seems that the potential canonization among Sunni, Shiite, and Kurdish factions, the disintegration of the territoriality of a bounded state provides a poor analogy for the sorts of sectarian division that we are likely to see: while it might be opportune for the West to imagine an oil-rich Shiite stronghold in the heart of Southern Iraq, would the concentration of wealth or resources in any way benefit the society as a whole or at large? If, as Robert Worth has suggested in the New York Times, “greater power . . . ultimately . . . devolve to provinces and cities — a process that has already been underway since the Arab uprisings,” is the sort of de facto partition of Iraq, a nation that has existed some ninety years, into Sunni, Shiite and Kurdish districts. This is the same sort of sectarian war that ISIS seeks to incite. Such increased parcellization of regions not only risks the stoking of ethnic animosities, but if analogous to the sort of “controlled burnings” of forest fires, to destabilize the region rather than serve the interests of its inhabitants. We surely seem to impute a oppositional divisions among Shia militias and Sunni groups than may in fact exist.

These divisions are not at all so clear on the ground, or perhaps so clearly beneficial to anyone in the long- or short-term: there seems to be a fomenting of religious divisions among a region, but perhaps the continued resort to a drawing and redrawing of lines to create a sense of unity offers the least chance of clarity or resolution. We have, in the West, perhaps performed something of a sense of collective amnesia, in our evocation of Sunni and Shia animosities, and Kurdish separatism, of the huge divisions of destabilization that we have so readily performed on the same territory in the more immediate past. Even the most recent invaders of the region appear unlikely to remember the instability and geopolitical disruptions that have so deeply undermined the region’s political coherence. One might more meaningfully and profitably look at far more recent maps to begin to map the continued destabilization that has recently played out across the region as a whole. For these divisions not only re-wrote the administrative divisions between the regions in the Ottoman state’s provincial borders–although it recalls the division between Mosul, Zor, Basra, and Baghdad, now redesigned to encompass the desert regions west of the Euphrates around Baghdad as if it were Berlin–but failed to respect the differences on the ground that Iraqis faced in seeking to act as administrators of a “new” land of ancient divides.

The above map of the occupying forces of Iraq were not explicitly directed toward Syrian territory or sovereignty, but created a site of desirability and destabilization from which future divisions of the region–and the relative success and difficulty of ISIS (or ISIS) must be mapped, as well as the hunger for a New Caliphate. For what is a New Caliphate, but a recuperation of an ancient dream of peaceful unity? Some years ago, Syria’s 92-year-old mufti quickly issued religious edicts that called for Syrians to fight in Iraq and sanction suicide operations against the Americans and their allies even though he was a renowned man of peace, as his words, with those of other clerics, inspired men from Aleppo, Damascus, and elsewhere in Syria who became the prime exponents of a jihadist movement. Their maps of regional organization, as much as the maps of military control, are worth our attention and investigation.

It is very thoughtful and, for me, informative Dan–bound, of course, to be controversial. But I learned a lot, thank you for this. I keep thinking about the “Jewish state” or the borderless Catholic state (unless you mean the Vatican state–that has borders but I mean the community of Catholics) that is under the rule of a papacy that has been stripped of military power only relatively recently, and it changes the way one might talk about a Caliphate (although nobody is talking about it in this context, I don’t know why). I am not in favor of any religious state, but we certainly have them in various ways, don’t we?

Daniel, you make a clear case for the irrelevance of cartographic boundaries in the Middle East, but maybe could go beyond this to the actual destructive effects of western imperialist sectioning. This dates back to the Roman empire’s conquests, to Pompey in 64 BCE. Oil didn’t yet figure, but eastern Mediterranean ports and trade routes did.